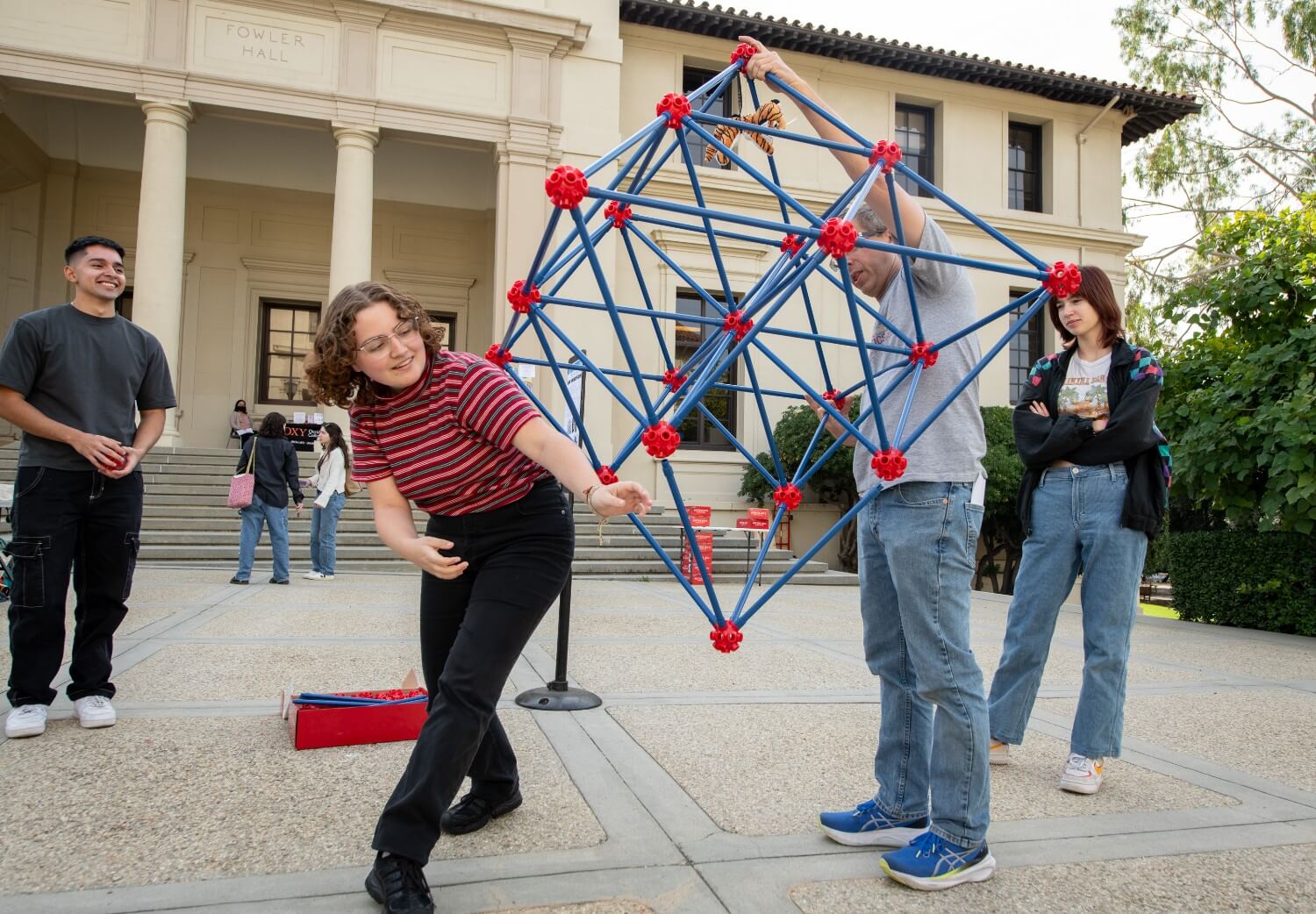

Waves of students and community members joined in constructing a towering, 17-foot-tall Sierpinski octahedron dubbed the “Oxyhedron” between Fowler Hall and Johnson Hall Nov. 10. Designer Glen Whitney, founder of the National Museum of Mathematics, said he has designed and constructed large Sierpinski polyhedra, three-dimensional recursions of regular polyhedra, in the past. According to Whitney and participating students, the Oxyhedron served to foster unprecedented connections between community members from across academic disciplines, display the beauty of math and change preconceived notions that mathematics is confined to numbers on a page.

Both Mathematics Professor Jim Brown and Whitney said they had apprehension about having enough volunteers, whether they were students or from the larger Occidental community. Nonetheless, the first cohort of volunteers congregated shortly past 10 a.m, which Whitney said cued his introduction on the background and logistics of constructing the Oxyhedron.

The Oxyhedron is a Sierpinski octahedron, a fractalized octahedron consisting of infinite iterations of itself. An octahedron, a diamond-like solid with eight triangular sides, is best pictured as two square pyramids sharing a base and may be familiar to those who have encountered octahedral dice. It is categorized as one of five existing platonic solids because of its perfect symmetry, something Plato claimed corresponded with the five elements, including quintessence, the fifth element of the heavens. The fractaling of the Sierpinski octahedron occurs by placing octahedrons scaled by one-half into each of the Oxyhedron’s corners. This creates visibly large gaps in the Oxyhedron, revealing a two-dimensional Sierpinski triangle — a triangle subdivided into recursions of triangles — on each face of the structure.

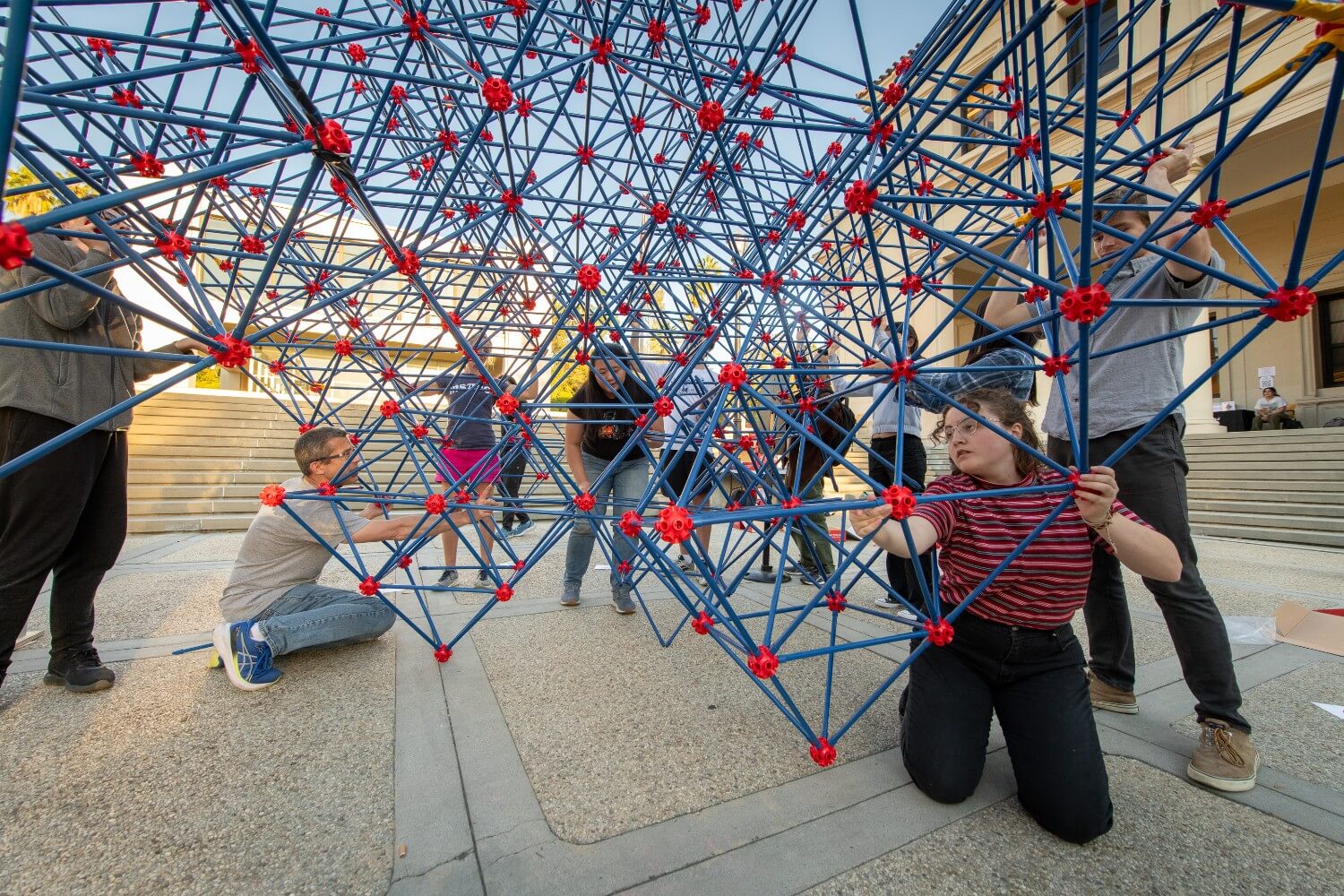

The first cohort witnessed as a miniature Oswald was tied around the waist to the vertex of the first, smallest-scale octahedron. Whitney said that they would build the Oxyhedron top-down, continually inserting additional modules as the structure gradually lifts itself up. Groups of two to three students worked on octahedral fractals, which were then individually added to the bottom of the existing structure until seven levels were achieved, according to Whitney.

Student volunteer Aaron Zemelman (first year) said this aspect of collaboration was one of the biggest benefits of the Oxyhedron’s construction, bringing together students from a wide variety of disciplines. Zemelman also said it broke down communication barriers between students and professors.

“I hadn’t met any of the math professors before,” Zemelman said. “Students were actively giving input into a project. That is really helpful for students [in order] to break down that power dynamic and realize that their voice and thoughts matter.”

These personal connections were also a way to begin understanding fractals, according to Zemelman.

“I find fractals fascinating,” Zemelman said. “When you make a subject really engaging and fun, and you’re also doing an activity with people that you really like being around, it just makes you more connected to the subject.”

According to Whitney, one of the intentions of bringing the Oxyhedron to campus was to show the beauty of mathematics, which is what motivates most mathematicians to do math.

Exhibits at the National Museum of Mathematics show how art and math are connected through discovery. For example, origami artist Joel Cooper equates finding combinations of folds to finding an elegant mathematical proof.

Brown, who teaches Abstract Algebra, said geometry is not his area but that he enjoys math because of the ability to harness new knowledge wherever you are.

“I like it in the sense of when I prove something new in the moment, I’m the only person in the world who knows that,” Brown said.

Brown said the Oxyhedron should demonstrate that there are multiple facets of mathematics that students and community members can appreciate. According to Zemelman, the Oxyhedron was effective in doing so.

“I think a lot of people don’t enjoy math because they think it’s so conceptual [and] you just have to think about it in terms of equations on a page,” Zemelman said. “This is a really good opportunity to take it out of just the page and into real life and make it collaborative. And I think that needs to be done more often.”

Whitney said this reframing of math was the core intention of the Oxyhedron.

“The hope always is that this disrupts people’s conceptions of math,” Whitney said. “This is something that’s not at all about numbers. It’s about the way things relate to each other in space.”

According to Whitney, one of the special components of math is play, not only with ideas but also with things like math-ish toys, such as a Hoberman sphere from a collection in his office. He said he must think about revealing new experiences in the observer of his design.

“I ask myself, ‘Could this be something that can be used to bring out some of the aspects of math that people don’t necessarily get a chance to see in their everyday lives?’” Whitney said.

On his package of the Ultimate Fort Builder, a children’s toy kit with the materials to constitute the Oxyhedron, Whitney said there was a blend of familiar shapes that would be amenable to the structure he intended to build. He said his main apprehension, though, was the ability for the colossal structure to balance on a single point.

“Settling it back down into the cradle is the moment of truth. I’ll definitely sleep easier after we’ve gotten to that moment,” Whitney said.

According to Ricardo Lopez, an employee of Tesseract Management who constructed the cradle for the Oxyhedron, working in multiple spots in tandem with the unpredictable tension made complications arise.

“[If] somebody on [one] end pops something out, something pops up on [another] end,” Lopez said. “Trying to get everybody to work together is just very hard. It’s so many connections.”

After absorbing the psychedelic view from below the structure, students and community members grasped the vertices and slowly raised the Oxyhedron in unison to place it in its cradle.

Not before taking a moment to capture the essence of the towering fractal, the volunteers simultaneously let go of their hold and watched as their creation collapsed back into its original elements.

“It totally sparkled,” Zemelman said. “[It was] a reflection of reality that not everything works out perfectly.”

Contact Yanori Ferguson at yferguson@oxy.edu

![]()

[…] a Sierpinski-style fractal based on the regular octahedron. You can read more about it in the The Occidental weekly newspaper; more details will be posted here as time permits. But here’s the completed […]