Eli Chartkoff took out an antique EIKI film projector from under his office desk on the third floor of the library. From the outside, the projector resembled a large green toolbox. Inside, two speakers were attached to the shell, and a variety of knobs, rollers and lenses packed the machine. Then, Chartkoff installed a reel of Kodak film, and a beam of bright yellow light emerged. He took a piece of A4 paper, positioned it right in front of the lens and readjusted the focus until a man wearing a yellow tank top and red shorts was visible. It was footage from the 1955 student registration day. However, after a short while the images disappeared and the film ripped into pieces.

“This has ripped in the past, and somebody just stuck some tape on it. It’s not really a permanent solution,” Chartkoff said.

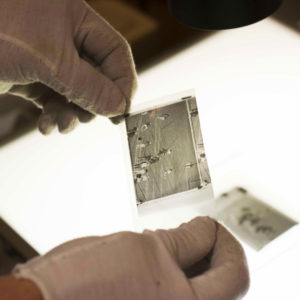

As a digitization specialist, converting film reels into digital files is only part of what Chartkoff does. He also photographs film negatives and digitizes cassette tapes and records. However, Chartkoff does not work alone. He is a member of Occidental’s Special Collections and College Archives.

Special Collections has four permanent staff members: Chartkoff the digitization specialist; Helena de Lemos, the Special Collections instruction and research librarian; Anne Mar, the assistant college archivist and metadata specialist; and Dale Stieber, Special Collections librarian and college archivist. The staff acquires, catalogues and maintains a collection of approximately 100,000 items used for teaching, research, media and marketing purposes. Stieber said by collaborating with students and faculty, Special Collections has an active role in shaping the identity of the college.

The Past

According to Stieber, Special Collections originally did not exist as a separate department within the library during the 20th century.

“Over the mid- to the end of the 20th century, the college librarian oversaw and connected with the the administration to gather and make sure materials were preserved,” Stieber said.

Richard C. Gilman and John Brooks Slaughter — presidents of Occidental College between the 1960s and 1990s — both felt strongly there should be a designated college archivist, according to Stieber. In response, Jean Paule, the then-secretary of the college, became the first archivist at Occidental in 1995. Originally, the Special Collections librarian and the college archivist were separate positions held by two people, according to Stieber. Paule served as the archivist while a man named Michael Sutherland worked as the designated librarian from 1971 until he passed away in 2005.

Stieber arrived at Occidental in 2004. She said her initial purpose at the college was to work on a special project related to the relocation of Japanese American students. She became a candidate for the Special Collections librarian in 2005 after Sutherland’s passing. Chartkoff also joined Occidental and worked in the collection services department in the library to repair and preserve books in 2005, according to Stieber. The other two Special Collections staff members joined at later times — de Lemos had worked with the department on short-term projects since 2006 and Mar joined following an administrative reform in 2010, according to Stieber.

The space they work in also has a history of its own. Special Collections is located on the third floor of the library. Behind the door lies a space about as big as a classroom, with 16 chairs, a few large tables and two glass shelves housing selected holdings. President Barack Obama ’83’s memorabilia adorns one set of shelves; opposite it sit handmade artists’ books with paintings and poems. Further inside, a bigger room houses all of Special Collections’ holdings, ranging from books printed in the 1600s, hand-drawn blueprints of campus buildings by architect Myron Hunt and a full collection of board of trustees meeting minutes since 1887.

According to Mar, the Mary Norton Clapp Library went through an expansion in the 1970s and the current space was built during that period. Mar said before the expansion, books and artifact donations were not systematically archived but instead scattered around offices in the college. By establishing a physical space to house these donations in the 1970s and funding permanent positions such as the college archivist in the 1990s, Special Collections gradually morphed into its current form.

The Present

Today, Special Collections provides primary source materials for classes, digitizes films and other analogue materials and assists professors, students and outside scholars with their research.

According to Mar, not everything stored in Special Collections will be kept. Mar said the department is currently reassessing its collections to see if they will, or will not, match the educational needs of the college. Holdings that do not suit the curriculum of the college are given away.

“There were some collections that have been either acquired or given to us over the years that we can’t do its service,” Mar said. “We had an aviation collection; we don’t have an aviation program here. So we were able to find another library in town that can serve it much better than we can.”

Besides donating holdings that do not match the curriculum, Special Collections actively acquires items to cover a wider range of curricular needs at the college, according to Mar. Mar said the staff find these items by visiting booksellers and book fairs, as well as using the professional network of collectors and librarians they have maintained over the years.

“We get visits from booksellers, who actually come and [are] kind of like a salesperson. [They] have a suitcase full of rare books, and we just pick and choose,” Mar said.

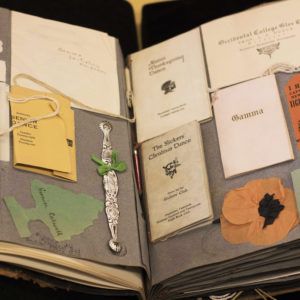

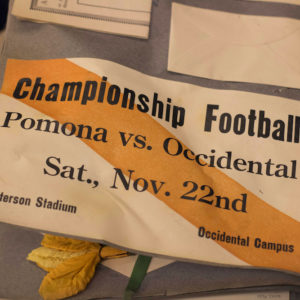

Despite giving away items, Special Collections still holds an incredible amount of books, records, photographs, films and tapes. The collection also includes specialized artifacts such as a functional Edison phonograph, as well as numerous scrapbooks that hold invitations, letters, corsages and certificates that students have accumulated during their time at the college.

Mar said she does not yet know the exact number of physical items stored in Special Collections because of the reassessment, but it is probably less than the 100,000 estimate made by Paule back in 2008. Chartkoff said he digitized a portion of the films and records in the collection since 2011, and the overall file size is already 30 terabytes, or approximately 500 days of non-stop video. He maintains a Vimeo page for digitized films and a SoundCloud page for digitized cassettes and tapes. According to Chartkoff, there are still many holdings that can be digitized; once completed, they can easily double the current storage. Chartkoff said certain film collections, such as ones donated by photographers, can be very large in size.

“We have just one collection of photographs from a local news photographer that’s over 100,000 negatives, and that’s just one collection,” Chartkoff said. “If you added up all of the photographs with the college archives, it might be half a million.”

According to Mar, some of the major users of Special Collections materials are college staff in departments that do outreach work such as the Office of Marketing & Communications and the Office of Institutional Advancement. With such a large number of items, it can be difficult for Chartkoff to pinpoint materials that would suit specific requests. This is when Mar comes in with her metadata expertise. Metadata is information that can be used to locate files, such as author name and publication date.

“All those digital objects need metadata or else, you would not be able to find them again. So we use a FileMaker Pro database to discover our digital collection,” Mar said.

Professors and their students also frequent Special Collections. De Lemos and Stieber play an instrumental role in reaching out to professors and responding to material requests, according to Mar.

“They build up this reputation of instruction-program where they can tie in original material with courses,” Mar said.

According to de Lemos, Spring 2020 is the first semester where she did not have to reach out to professors to see if they wanted to incorporate Special Collections materials into their courses. Instead, professors came to her to ask for materials related to their teachings.

“They already have in the syllabus — in their planning of classes — that there is going to be a visit,” de Lemos said. “It’s already incorporated and they [professors] are already having new ideas.”

Biology professor John McCormack is one of the faculty members who has taken his classes to Special Collections. McCormack said de Lemos initially reached out to him and introduced him to the Special Collections resources.

“She reached out to me for the evolution [biology] class, just inquiring that there might be a good match there for taking my class into the collection,” McCormack said. “After we did it, it was such a hit that I decided to expand that [visiting Special Collections] to my other class.”

McCormack said the first time he took a class to Special Collections was in 2016. Since then, he has taken five more biology classes there. In Fall 2019, he took two evolutionary biology classes to the collections. McCormack said science courses may not seem like a great fit for Special Collections, but there were many relevant materials in the holdings.

“Evolutionary biology definitely has a historical component to it that I always taught in the first couple of weeks in the class,” McCormack said. “So the books in Special Collections, from an old edition of ‘The Origins of Species’ to even older books from the 1600s talking about viewing science from a religious angle, could walk [students] through the development of thought leading up to evolution.”

According to McCormack, the Special Collections room would have four tables or stations for his class, each containing six historical books. Students could rotate around each station to study the materials closely. Ellie Furth (sophomore) was a student in the evolutionary biology class. Furth said reading those books was a great opportunity to have, and she especially enjoyed interacting with primary materials.

“It was particularly fun to be able to physically touch and smell the books,” Furth said. “It transports you back in time.”

Music history and cultural studies professor Edmond Johnson also incorporates Special Collections material into his classes. When Johnson arrived at Occidental in 2011, one of the first things he did was introduce himself to the staff at Special Collections and ask whether there were materials that would work with his classes. Johnson said he recognizes the value in primary resources and historical objects from his past experience working with special collections and thought they would enhance students’ learning.

“My background is as a music historian, that’s what my PhD is in,” Johnson said. “I have a lot of experience doing archival research. When I was a graduate student at UC Santa Barbara, I actually worked in their Special Collections for six months.”

Johnson teaches a cultural studies program (CSP) seminar every spring called “Exploring the Cultures of Recorded Music.” The class focused on recorded music from the 19th century to the present. However, inside Special Collections, Johnson introduces students to manuscripts that predate the phonograph by many hundreds of years.

“The phonograph was invented in 1877, but the earliest thing that we have out on display for the class was from 1200, 670 years earlier,” Johnson said. “What we’ve decided [is that] if you’re going to tell a story about music technology, it’s worth talking about how did we capture music before the phonograph. So we bring out these old, handwritten manuscripts of chant and religious music and talk about the difficulties people would’ve had in recording, performing, and transporting music.

With a limited work space and four permanent staff members (plus a few voluntary, unpaid student assistants), it can be overwhelming at times for Special Collections to handle the large amount of class and research requests. For example, Mar said Special Collections hosted roughly 50 class visits between the 2018-2019 academic year.

According to Mar, Special Collections’ staff of four is fairly small for what the department wants to accomplish.

The Future

Mar said she hopes there can be paid interns at Special Collections, allowing the department to transform into a more comprehensive primary research center. However, she understands this will probably not happen in the next few years due to limited funding. Chartkoff said he would not be able to digitize as many films as he wants because it is an expensive service that can only be done on off-campus sites. Instead, Chartkoff said films and negatives are mostly digitized on demand. And according to de Lemos, having only one room for class visits means sometimes classes with two sections, or with more than 16 students, will have to visit Special Collections at separate times.

Stieber said Special Collections needs to have larger collections and bigger work space. Most importantly, Special Collections also should have a role in collaborating with students and faculty to shape the college’s identity. For example, Stieber said when Mar was working on assembling a Black History Month exhibit, the involvement of a student resulted in the best selections. In another instance, history professor Jeremiah Axelrod said the collections inspired him to create the Institute for the Study of Los Angeles (ISLA) .

“One of our projects that I most care about is the use of examining the college history, contributing it with students’ perspective, and evaluating it,” Stieber said. “[It’s] not just us always pointing at pictures, and saying ‘This is the history.'”

![]()