The community of military life

One mile west of Occidental College, atop a hill with a sweeping view of Eagle Rock and the San Gabriel Mountains, live four Occidental student veterans and one of their partners. The Toland Way housing complex, which was purchased by the college in 2018 and welcomed its first student veterans in spring 2019, is designed to “provide community and a sense of place for Oxy’s veterans,” according to Occidental’s website. For many student veterans, “community” is not merely a buzzword but a necessity — it is both their remaining connection to military life and the first tie that is severed when they leave it, according to Nathan Graeser, Occidental’s new director of veteran programs. An Army chaplain, social worker and service member, he has extensive life experience mingled with an unmistakable spirituality in his manner — each story he tells seems to hint at a dozen more.

Graeser was a high school senior from Indiana when he joined the military in 2000, enlisting with a close group of friends and enrolling at Indiana University Bloomington while awaiting deployment. This was the beginning of a period of limbo: while some of the friends he had enlisted with were deployed, his own deployment date was continually pushed back, leaving him unsure of his next steps. His confusion soon gave way to turmoil.

“About four months before we graduated, I got a phone call that [my best friend] Brett had died in Afghanistan. He had just come home that Thanksgiving. He was engaged. I was devastated,” Graeser said. “I thought, ‘Wait, what? Is this what the world is like?’”

Brett’s death uncovered a sense of loss in the world that Graeser said he did not yet understand. Seeking to know what the world was like for his unit returning from war, Graeser began to listen to these soldiers’ stories.

“My unit was coming back all messed up. We basically brought them in from war and then said, ‘Good luck,’” Graeser said. “They were getting DUIs. Guys I knew were hitting their wives. I was sitting there pouring coffee, listening to people. I did it so much I felt like I was a professional coffee pourer.”

Graeser was far from finished listening to others’ stories. The experience inspired an epiphany about the path he wanted to take, he said.

“At the end of that summer after I graduated, I knew,” Graeser said. “I was like, ‘I don’t want to be an infantry officer like everyone wants me to. I’m gonna help soldiers. And so [people said] well, that’s what chaplains do. So that’s what I did.”

In Graeser’s work as a chaplain — providing spiritual and faith-based support to soldiers while enlisted himself — he began to notice a persistent problem affecting many of the veterans and families he worked with: a lack of community.

According to Pew Research, less than one percent of the U.S. population is currently on active duty, and less than 10 percent have ever served in the military.

“The military is becoming a smaller and smaller, more exclusive force. So functionally, what that means is that most people will never know someone who’s in the military,” Graeser said. “The first effect of that is that it insulates the rest of the world from the effects of war.”

Behind Graeser’s desk is a shelf on which stands alone as if on a spotlight the plays of the ancient Greek playwrights: the tragedians Sophocles, Euripides and Aeschylus, and the comic Aristophanes. Shared among them is their setting in the Greek polis. The polis was the structure of the Greek way of life wherein the absence of a monarch bound society together, each life affecting and being affected by the other. This is in stark contrast to a typical American neighborhood today, with its spread-apart homes, solitary pursuits and inhabitants who go to great lengths to ensure individual success and avoid confrontation. According to Graeser, this is part of why he loves the Greek texts — and part of why veterans struggle so much returning to this society.

“The bond that you make in war is so intense; it’s deep love. It’s like self-sacrifice. Every one of them will give their life for the good for the whole,” Graeser said. “The other person stops becoming another and they become a part of you. They know things no one knows about you, intimate things you share with each other at night. When you think you’re going to die.”

In progressive American society, which, for better or for worse, greatly emphasizes individual expression, people often place their personal, political and intellectual differences on a pedestal, according to Graeser. This is in stark contrast with military life, however, Graeser said.

“[There,] your ideology doesn’t matter as much as you might think it does; you have to know that our futures are tied to each other and that I don’t care if you’re Republican or Democrat,” Graeser said. “I was deeply formed by these people. My first real conversations around race and culture were with people on a toilet up to each other, because there were no stalls in the bathrooms. Talk about intimacy, right?”

According to Graeser, as veterans exit out of the polis of military life, they may struggle to find community in a country where loneliness, according to many, is an epidemic.

“Vets have this experience and they get out of the military and come to a super isolated place. I struggle to connect with my best friends, even my wife. We all have so much to do,” Graeser said. “We get something out of [this individuality]. But it’s not what we actually really crave. What we want to be is known and seen and felt. But most of us don’t know how to do it.”

This sense of being socially and physically bound to one another is built into the small college experience, Graeser said, and is part of why he believes Occidental is a good school for veterans.

“It comes full circle back to Occidental,” Graeser said. “College, like the military, forces you into these environments where you’re forced to be with people who are totally different, who smell different, act different and come from different backgrounds. At some colleges I [as an administrator] can send an email and not see the results of it for weeks. But here, my work and my future is tied to everyone else.”

Occidental as a community

Alexander Borges (junior) is one student veteran who also sees the interconnectedness between military life and college. Growing up in Queens, NY, Borges graduated high school in 2014 and became a Marine Corps reservist, balancing everyday work life with the possibility of being called into service on any given weekend. Having experienced military and civilian life simultaneously before enrolling at Occidental, he realized how similar these communities can be.

“[Students and soldiers] both are in this weird situation where you get thrown in, where you don’t really know anyone,” Borges said. “You’ve got this sort of shared experience that makes it a lot easier to make friends, and almost everybody’s around the same age. The connections you make are a lot more meaningful than, for example, when you go into your first job.”

As a Barack Obama Scholar, Borges receives not only a full scholarship to attend Occidental, but a cohort of mentors to guide him and help develop his goals. The scholars program hosts events such as career readiness workshops and challenging discussions on black feminism in America, Borges said. This led him to cite yet another similarity between military and college life.

“You are set up for success because here in college, just like the military, there’s people looking out for you. And there are people that care about your success and want to push you forward,” Borges said.

According to Borges, veterans often would not initially think of liberal arts colleges as a main choice, in part because of their high sticker price, reputation for radical politics and relative obscurity compared to larger state schools. But Borges said Occidental’s supportive environment dissolved those preconceptions.

“College can be this crazy, daunting experience because you’re coming from this environment where you know how things work, and now you have to go to this different sort of set of institutions and try and figure things out,” Borges said. “‘How do I get a transcript sent out? How do I get my financial aid done?’ Especially considering a lot of veterans are first-generation college students. So there is a lot of support needed, and Oxy provides it.”

What many veterans are looking for in civilian communities — be they colleges, workplaces or neighborhoods — is a sense of shared life and support, according to Graeser. However, this is very rare, Graeser said.

“Most vets will come out and get a job and the first thing they tell me is, ‘This is a job,'” Graeser said. “They go, ‘I don’t want just a job. I want a lifestyle, a mission. I want a place my soul bleeds for, where these people are our brothers and sisters, no matter where they come from.’”

Supporting and educating veterans has always been part of the college’s ethos, according to Jim Tranquada, Occidental’s director of communications and community relations.

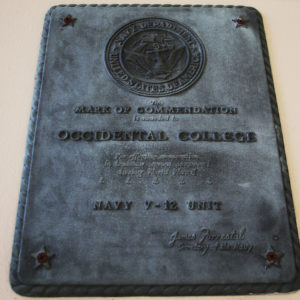

“Oxy alumni have served in every conflict since World War One,” Tranquada said. “So we’ve had veterans on campus for 100 years. During WWII, we had a V-12 Navy program from 1943 to 1945, which was an officer training program where hundreds of Navy recruits were brought to Oxy to finish their officer training here before they went on to active service.”

Occidental also built veterans housing where the Facilities yard is today and housing for married student veterans where Berkus Hall now stands, according to Tranquada. Occidental has been supporting veterans through the Yellow Ribbon scholarship program for the past 10 years and has consistently been designated a Military Friendly school. However, it is not only veterans who benefit from being at Occidental, but the other way around as well, Tranquada said.

“Because of their service and because they’re older, veterans oftentimes have a really clear idea of what they want to get out of their education. They’re very directed and they’re very focused,” Tranquada said. “They bring a different perspective to campus because of the experiences that they’ve been through.”

Veterans and the world community

None of this is to say, however, that it is always a smooth transition for veterans (many of whom are nursing psychological or physical trauma) to come to a predominantly privileged community of much younger students, Graeser said.

“They jokingly call themselves the old men in their class since they’re sometimes 10 years older,” Graeser said. “And you can imagine if you’ve been in war multiple times, and you’ve had some really crazy, hard-fought lessons in life, then you sit in a class and someone says, ‘I’m experiencing violence,’ sometimes you might think, ‘That’s an interesting definition.’”

Yet Graeser also described Occidental students’ fierce commitment to protecting each other as an admirable, natural part of the cycle of change. Each generation of young people aims to build better communities and to fix what their ancestors could not; this is what it means to come of age, according to Graeser. For veterans as much as for first years fresh out of high school, a balance of ideals can help ground them while propelling them forward.

“Often, liberal arts colleges are desperately trying to ground their student bodies in reality, while also fueling them to take action against the problems in the world,” Graeser said. “Even the mission of Oxy is to prepare you to take on the most complicated, enduring challenges. And in many ways vets, when they come to the school, have really, really challenged themselves. They provide a counterbalance.”

Coming out of the rigidity of military life, many veterans go onto civilian institutions that are highly structured, Graeser said. According to Graeser, college provides a different kind of bastion for veterans: a place to ask questions.

“In war, you’re just surrounded by horrible things. People come out angry and sad and with huge questions,” Graeser said. “Like, ‘How did we do that? How did we get here? How are we still doing this? How am I going to do anything about this?’”

Graeser said he believes Occidental’s culture helps students explore some answers. Through the Barack Obama Scholars program, for example, Borges said he is taking a philosophy seminar on what it means to live a good life.

“We have an environment that’s very conducive to self-discovery,” Graeser said. “It’s encouraging to new ideas. Think of how different that is from the military. There, you don’t get to have new ideas. No one is asking you your opinion on things.”

But one of the hardest and most enduring questions in history, Graeser said, is the one that haunts some veterans the most: the problem of evil in the world.

“Recently we’ve been using the term ‘moral injury’ as opposed to post-traumatic stress disorder, because it tracks better with veterans’ experiences,” Graeser said. “It is as if my rights or morals were violated. Not just by my experience, but by the leadership, by people I interacted with, by what I was supposed to have that I didn’t have.”

Graeser trained as a chaplain at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, a place where he was constantly learning to read, write and think about evil. Contending with evil, he said, enabled him to find his own way to understand and ready himself against it.

“When we’re hurt, or someone does something to us, the reason that it hurts us is not because it’s a new thing in the world. Like, if someone steals from you, thousands of people are stolen from every second,” Graeser said. “Whether it’s murder or assault or grief, this is just your invitation to this suffering that already exists in the world.”

Even when speaking about the most devastating experiences a human being can have, Graeser smiled with ease, frequently glancing out the wide window of his sunlit Toland Way office. His voice was intense and earnest, but he was able to laugh, to tell funny stories about his family, to gesture wildly. This fundamental sense of peace arises, Graeser said, from an ability to wrangle with the human capacity for pain, rather than shield himself from it in fear.

“In the veteran space, when a parent loses a child to suicide, almost all of the moms I met start nonprofits right after. They raised so much money, started becoming advocates,” Graeser said. “It’s not that before this happened they did not know suicide was a real thing. But when we’re traumatized, we’re connected to it and the suffering that already exists comes into your orbit.”

Borges, who was drawn to the Marine Corps partly for its humanitarian spirit, said he recognized this inner strength and generosity among his fellow service-members.

“The Marine Corps is one of the most used resources during humanitarian disasters. The response in New York City after Hurricane Sandy by the Marines really inspired me,” Borges said. “I spoke to these really experienced people who had been through hell on earth and had a different understanding on life. I learned from them not just about being in the military, but also about being a productive member of your family, being a good father, living a good life.”

Graeser described these people, who recognize their sorrow and channel it for good, as having an arc: a resilient inner structure that guides them to understand and undergo suffering. The worst disservice society can do to veterans, Graeser said, is to strip them of their power and arc.

“We make vets victims a lot. We take all their power away. We soften the evil they’ve seen. But veterans can contribute so much,” Graeser said. “They just need a container, like for a plant to grow. I think of vets as oak trees in most communities. They’re the ones who vote against bullies. Once they’re planted there, these folks are self-sacrificing.”

Graeser glanced again at the Greek texts behind him as he spoke. American veterans, he said, often have journeys that mirror those of the Greek warriors. Like Heracles and Ajax, they often must grapple with failed homecomings, ethical quandaries and the struggle of finding community after seeing the world torn apart.

“As a veteran, your most heroic moment is sometimes next to one of your worst moments. They learn to recognize fear and channel it,” Graeser said. “Veterans have this deep sense of responsibility. They have a sense of the evil in the world, and they protect their communities from it.”

This article was corrected Feb. 19, 2019 at 1:35 p.m. to reflect the correct spelling of Graeser’s best friend’s name.

![]()