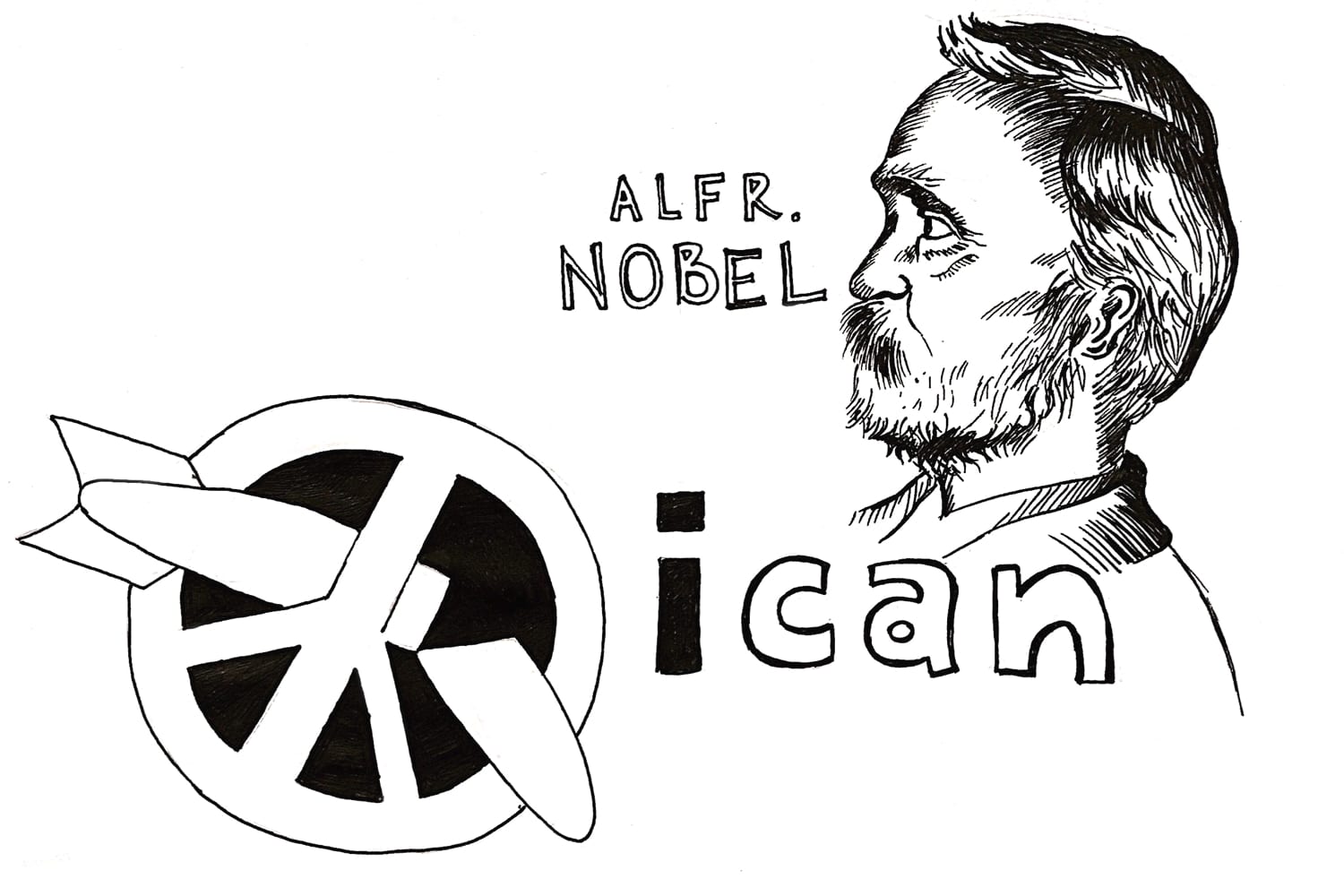

The Nobel Peace Prize is widely considered to be one of the most prestigious awards on the planet. Members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, who choose the recipients of the Nobel prizes, have a tremendous amount of power to promote and reward virtue in the world. However, the selection of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) for the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize is the latest of myriad examples of the prize being squandered. Over the past decade, we have seen more recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize chosen for political reasons than their contributions toward peace.

Choosing the person who most helped the world move towards peace is a tough job, and mistakes are inevitable. It’s hard to quantify, and it’s rare that there are breakthroughs in the field of peace like there are in physics or chemistry — two other Nobel Prize categories. However, the Nobel selection committee’s vague and wavering standards for the Peace Prize devalue it. Nobel Prizes should be given out for achievement, not for potential achievement.

The elimination of nuclear weapons is a noble idea and an important one, but clearly it’s not going to happen anytime soon. This is one circumstance where ideals must bend to reality. There are too many states with nuclear weapons, too many countries that want the veneer of safety that the doctrine of mutually assured destruction provides. The principal achievement of ICAN is its success in lobbying for the Treaty on The Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, a treaty boycotted by the countries that matter in this discussion; all of the nuclear-capable states and almost all of the members of NATO abstained. Like many other legally binding pieces of paper the United Nations has produced, the treaty will be politely ignored.

Controversy over the choice of recipient for the prize is not unusual; the selection committee has made some serious mistakes. Mahatma Gandhi never received the prize, and in 1948, the year he died, the Nobel Peace Prize was not given out at all because of a lack of qualified recipients. When Henry Kissinger shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973 for his work on the Vietnam ceasefire, two committee members resigned in protest. When the ceasefire failed, Kissinger tried to return the award. Most recently, Burmese leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who received the prize in 1991, is currently presiding over the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya people in Myanmar.

It is also unclear what the Nobel Committee’s standards are for awarding the prize. The selection of then newly-elected President Barack Obama for the 2009 Peace Prize baffled everyone, including Obama himself. When asked in a 2016 Stephen Colbert segment what the prize was for, he even joked, “To be honest, I still don’t know.” Obama’s first campaign and eventual election were meaningful moments for America, a time when hope triumphed over fear as we united behind our first African-American president. He had barely assumed office when he received the award.

And eight years later, we may wish for Obama back, but his legacy is not one of peace. As President, he greatly expanded the use of drones by the American military and failed to close down Guantanamo Bay after repeated promises to do so. Obama’s prize was an attempt by the committee to unite America and the world around him, and it failed. That’s not their fault, but it showcases the limits of their influence.

The European Union (EU) also won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012, which is patently absurd. However much anyone might believe that the EU is good for Europe and for the world, it’s ridiculous to give it an award for promoting peace. The elite of Norway giving a prize to their neighboring elite in the EU is self-indulgent and contrary to the spirit of the award. You might as well give NAFTA a prize for preventing war in North America.

Some theorize that the Nobel committee chose ICAN as a response to the belligerence between Trump and North Korea. Whatever the reason, while ICAN is doing important work that shouldn’t be ignored, it was not deserving of a Nobel Peace Prize. Awarding organizations like the European Union or ICAN or even the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons with the prize is squandering the opportunity to highlight the individuals and groups that truly deserve the prize. It’s not like there is a dearth of worthy recipients among the seven and half billion people in the world; people like Taner Kılıç, a founding member of Amnesty International in Turkey who is currently in jail for his work on civil rights. There will always be some measure of political calculus in the equation, but it’s an abdication of the Nobel selection committee’s influence for it to choose a large organization or a famous politician.

The Peace Prize should be a way of elevating the goodness in humanity, honoring the people that have helped make the world a better and safer place. At its most basic level, the Nobel Peace Prize is a pedestal that is only as good as the people we place upon it. Without clearer standards for earning it, the prize will become nothing more than some cash and a pretty medal for five Norwegian politicians to hand out.

Milo Goodell is a sophomore Politics major. He can be reached at mgoodell@oxy.edu.

![]()