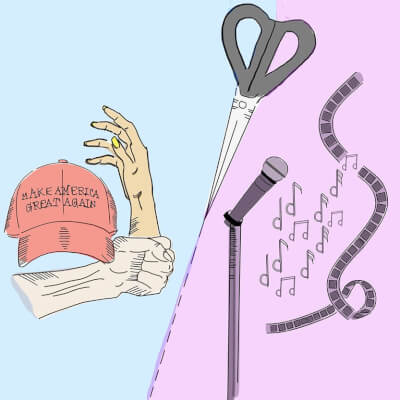

I first stumbled onto the Tumblr site “Your Fave Is Problematic” in 2014. I was biting into some unbelievably savory Chick-fil-A nuggets while listening to Chris Brown’s 2007 masterpiece “Take You Down” and wearing my go-to Nikes. I scrolled through the obvious problematic names, feeling indignant and inspired, and cheering in my head: “Yeah, frick J-Law! Boo Big Bang Theory! OMG, Lena Dunham is the worst!!!” As I scrolled on, though, something changed. I started seeing the names of my idols. My jaw dropped. Tina Fey? Donald Glover! Sean Penn!? And — perhaps the most devastating — Rihanna herself. I almost choked on those beautiful, golden-brown homophobic nuggets and I began to think, “Am I problematic?” I learned a valuable lesson that day: it really do be ya own homies.

More importantly, I learned that artists, even our favorite ones, are just as flawed as the rest of us.

In the age of Brett Kavanaugh and Bill Cosby, it is more important than ever to hold the powerful accountable for their actions. Yet at the same time, entirely disregarding an artist for their problematic actions isn’t a solution. In fact, it kills any possibility of moral growth. We are quick to idolize and even quicker to condemn. We can’t reduce a person to completely good or completely bad — they are both.

There is a new term for this extreme-ethics phenomenon, known in the Twitter-sphere as “You’re canceled, sis.” “Canceling” is when people decide to cease their own consumption of a problematic artist’s work. With the help of social media, this can snowball into a mob mentality bent on terminating the validity of a problematic artist’s work. This can be, well, problematic.

People cancel artists no matter the gravity of their offenses, like some one-size-fits-all panacea. The “problematic spectrum” could include those who made a misstep when they were young and have since recounted their statements; in 2009, Halsey tweeted that her makeup artist made her look like “a hot trani mess.” It could also include artists who aren’t explicitly problematic yet remain silent about their peers who are, like when Nicki Minaj chose to collaborate with sex offender 6ix9ine earlier this year. It can even go so far as to cancel any sympathies sent out to XXXTentacion’s friends and family following the alleged abuser’s death. These are radically different scenarios, yet are met with the same condemnation and overly dramatic canceling efforts. So often do we jump to these extreme, blanket solutions and neglect to consider the nuances of each offense. Frankly, it’s lazy and unfair. We must continue to ask ourselves if canceling is truly the punishment that fits the crime.

These gray areas are especially rampant in Twitter’s current cancel-friendly climate. Trevor Noah, the beloved ultra-liberal host of The Daily Show, is often considered a crusader of tolerance and “woke” politics. Yet in 2015, the public dug up some old problematic tweets, replete with anti-Semitic and misogynistic jokes. Suddenly, canceling Noah became a trend. The public was quick to label him as permanently problematic. Although freedom of discourse through social media is a dope display of contemporary democracy, this weird chauvinistic battle over who’s the most “woke” leaves no space for personal growth. Twitter icon Brother Nature, a recent example with problematic tweets from his tween years, put it best in his open apology: “I was a child and am now a man asking you to accept the apology of a young boy.”

I respect those who argue that canceling a problematic figure solves the problem of how consuming their work supports them financially. But I doubt Chris Brown losing $0.006 after I chose to not listen to his aforementioned hit “Take You Down” for the millionth time will really affect his affinity for domestic abuse. Nor will skipping a Halsey song magically prevent her 15-year-old self from using a slur on Twitter.

I’ll admit, I’ve wondered if I am betraying my own ethics by enjoying these problematic artists. Yet, I’ve never truly doubted my support for gay rights just because I fiend for Chick-fil-A nuggets, nor have I seriously questioned my aversion to exploitative labor practices just because I own an iPhone. Perhaps we hold the art we consume to such a higher standard than everything else we consume because we feel entitled — and when it betrays us, it stings. In our confused, ego-damaged state, we are quick to cancel the source of the pain, even if that means canceling its beauty, as well. To enjoy the genius of an artist, we must also acknowledge the evil of the artist. Contradictions are everywhere, and the more we hide from them, the less we grow from them.

All we can do is constantly interrogate ourselves and try to be better than we were yesterday — and give that same sympathy to our own problematic faves. If we really are what we eat, then maybe skipping a trip to Chick-fil-A every now and then is a good call.

And no, Sundays don’t count.

Ella Price is an undeclared first year. She can be reached at eprice@oxy.edu.

![]()