During the “Barbenheimer” cultural event, I dressed in pastels for Greta Gerwig’s “Barbie,” so I figured I might as well dress in black slacks for Christopher Nolan’s biopic on nuclear physicist and creator of the atomic bomb “Oppenheimer,” too. When I walked out of the theater, I felt the same way I did with most of Nolan’s films: that they were bloated, pseudo-intellectual and way too over the top. But then why was I almost crying?

Being an ex-physics major, I watched Oppenheimer four times, and “Can You Hear the Music” was my number one song of 2023, even though the movie came out in late July and Travis Scott dropped “Utopia.” I hate that I watched Oppenheimer four times because it is a movie about a man who disregards everyone around him and is generally and genuinely a terrible person who did terrible things; and the movie has little to no representation outside this aggressively masculine figure — as someone said in one of my seminars, it’s a “Ken movie.” Yet I couldn’t stop thinking about the movie.

What stood out to me the most, aside from the film’s hypermasculinity, was the less than two-minute montage of Oppenheimer in college, where, I saw myself for the first time on screen — a moment of pure recognition (not, however, I hope, the cliche, edgy and hyper-masculine “literally me” recognition that the film has incurred). In the scene where Niels Bohr asks Oppenheimer, who is losing himself in college, if he “can hear the music” (if he can see the beauty of physics, hence the theme), Oppenheimer responds, “Yes I can.”

What the movie never takes into consideration — even though we see Oppenheimer struggle to understand the world around him — is, well, what happens if you can’t hear the music?

By the Fall of 2021, the beginning of my sophomore year, I had already undergone a summer of physics research and was well underway in the introductory courses — Electricity and Magnetism, and Linear Algebra. It was the first school year since COVID. On one of those hazy, suffocating, autumn nights, I stepped out of the Hameetman Science Center after five hours of studying (which I had done the day before, and the day before…). It was a bit past midnight. At that time — things were different then — no one was in the Quad, so the friend who I would study with, another young physicist, and I would fill the quiet, scary, empty night telling each other of all of our doubts. The Quad was empty; so were we. Stepping out on the Quad after trying so long to understand the world — or the version of it the formulas presented — made it seem like nothing really existed; that, given the fact that everything was a (manipulatable) matrix, the ground and the sky were not divided, but squashed together, and my friend and I were suffocating in the spacelessness. (If it isn’t obvious, I spent a lot of the days that trickled away that Fall semester trying not to cry.)

One of those nights — and there were a lot of them, walking out into the quiet, empty Quad at midnight (and, of course, I had an 8:30 a.m. class) — I met another friend, another physics major. Again, as we spoke to each other, it seemed like nothing else existed — until their words cut through the airless-air (technically non-existent particles of air operating under the Doppler’s effect): “I bombed a test today.”

They stared at me wide-eyed; I stared back. Unfortunately, failing tests was a common occurrence for us, and I responded in turn: “I bombed a test this week, too.”

A lot passed through that glance: the burden of being a person of color in STEM, shared and similar intergenerational trauma, and the dwindling loss of hope that things would get better. We just stared.

Undoubtedly this was an experience for Oppenheimer in the film, too, who, not just fails on screen in his graduate level lab, but was also in complete awe — and therefore fear — of the infinite, expanding and uncontainable universe that physics presented him. I spent many a night that semester, cowering under my covers while equations played in my head, just like Oppenheimer. When in the film, Oppenheimer sees the electron clouds — quantum possibilities shining in blue in front of him — they are not beautiful, but imposing. And what I interpreted Oppenheimer’s feeling as he cries in bed, was exactly how I felt: If nothing exists but vectors, or quantum states, then all that could follow for me and the other young physics majors was the feeling, “Does all we do amount to nothing?” (speaking in linear algebra terms — do we only exist in the null space?).

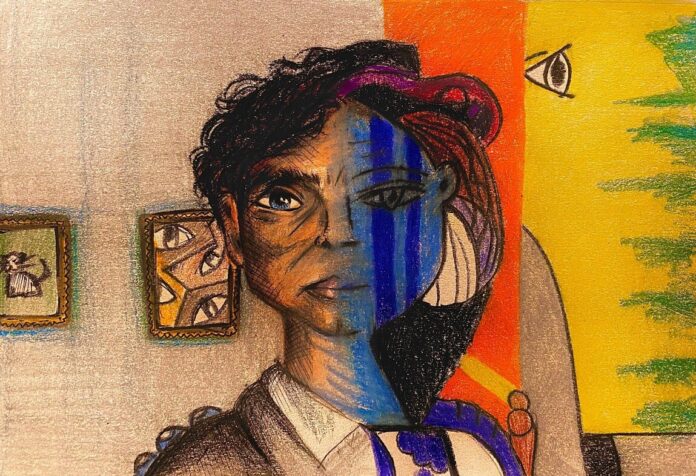

Perhaps this is why, in that same college montage, Oppenheimer finds himself at the museum, in Picasso’s “Woman Sitting with Crossed Arms” — the painting, itself a mirror. This scene is the most painful for me because it is evident that Oppenheimer is so much like the woman in Picasso’s portrait: cross–eyed. Always staring in different directions, one eye stares to the future, the other the past, one eye sees reality, the other the quantum realm we’re all lost in. And the price Oppenheimer pays for his dual vision — the ability to hear the music — is that he is unable to stare straight ahead.

That Fall semester, I was tired of seeing in both directions — as was my friend. Oppenheimer’s cross–eyed glance, it seems, was one of pure reduction, for in the quantum realm there were only probability matrices, not people. At that night — all those nights — I wanted to be a person, just like my friend. What I wish I could have told them then — and what separates me from Oppenheimer, who indulged in that cross-eyed nature, and did not see the human in others — was there was a world beyond the vectors. “You and I,” I should have said, “we are the same.”

Contact Sebastian Lechner at slechner@oxy.edu

![]()