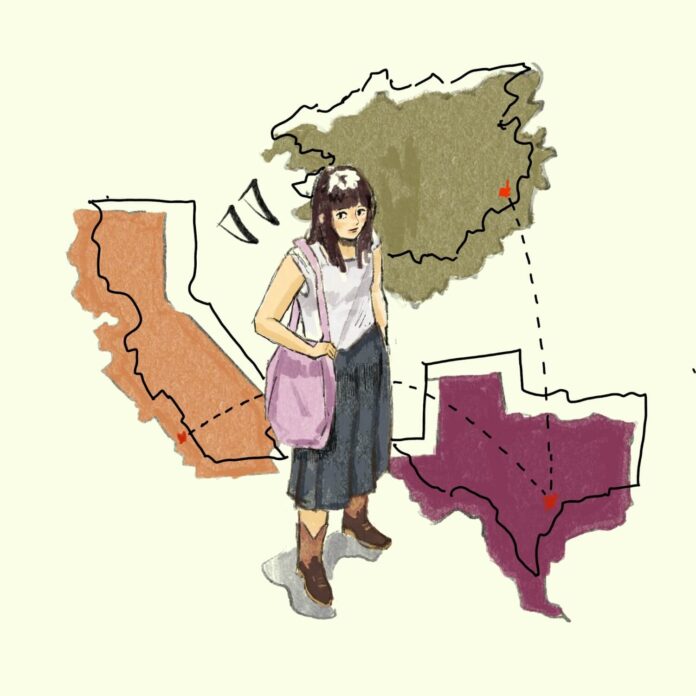

I like to refer to myself as “The Chinese Cowgirl,” joking about the weird mishmash of cultures I grew up in. I was born in Guangxi, China and grew up in Austin, Texas. I’ve experienced a plethora of things that can be found in one culture but are not seen in the other. I get that serotonin boost entering the giant Buc-ee’s in between Austin and Houston (if you know, you know). I’ve had my fair share of Chinese aunties telling me my Mandarin needs to improve. I throw in a “howdy” or “yeehaw” once in a while, even when speaking to people I’ve just met. I can poach the best egg you’ll ever have at an all-you-can-eat hotpot. Being adopted from China and moving to Texas so early in life but having American parents who prioritized immersing me in Chinese culture has created the most complex — but beautiful — cultural identity storm for me.

I tend to stay away from social media because it’s not worth my time but weirdly enough, I gained a new lens for analyzing my cultural identity during one of my late-night doom scrolls on Instagram. I stumbled across Vivienne Leow’s jewelry line. Leow describes herself as a “Third-culture creative exploring diaspora.” I poked around her page a little more and saw she had created a zine about her experiences bridging different cultures and her journey in discovering and reclaiming her cultural roots. I had heard of the terms “third-culture” and “third-culture kid” before, but Leow’s creative projects helped materialize the meaning for me.

“Third-culture kids” are individuals whose mixed identity reflects the culture of their parents, or home country, and the culture of where they were nurtured and raised. This term is usually used to refer to people who have moved to different countries. Seeing how Vivienne articulated her struggles of leaving Malaysia for Indonesia, and eventually America, I realized the parallels between our battles of defining ourselves in relation to our culture. I then asked myself, “Am I a ‘third-culture kid?’”

At first glance, my ethnic Chinese culture could not be more distant from the Texas culture that I was nurtured in. Growing up, I could be found tailgating for my high school homecoming football game one night but wrapping pork and chive dumplings the next morning. There is no real way of defining Southern culture — mac n’ cheese that gives you heartburn, front desk ladies who call you “sugar,” sitting outside on your front porch in 100 percent humidity summer heat sipping on a pitcher of sweet tea. The culture of my hometown inherently has nothing to do with the equally as familiar Chinese culture I grew up with — burning my mouth on xiao long bao, never learning to button the frog buttons on my qi pao and hanging Chinese knots on the walls that symbolize longevity and eternity.

My parents encouraged me to embrace the culture of my home country while also helping me understand the cultural history and significance of where I was being raised. Many a time you would find my family road tripping through the Deep South exploring and experiencing Southern culture. At the same time, they sent me to a Chinese school six days a week hoping I would connect with my Chinese roots and a culture they could not provide at home. Even though I don’t remember leaving China, I still feel this intense cultural connection to it, but I also equally embrace my Americanness. I’ve been living in between these two cultural worlds for as long as I can remember.

I’ve always felt that I had to separate my Chinese and American identities, but I’ve realized that these two cultures work in tandem to create an intricate third culture I use to identify myself. So yes, I would consider myself a third-culture kid. Through this third culture, I have made connections between two groups of people that seem far apart, but actually share so many similarities. Both of my cultures value family structure and have distinct food. Most of all, the people of both Southern American and Chinese cultures are empowered by uplifting others through storytelling and passing down customs. My cultural identity is rooted in the people and experiences I surround myself with rather than the places I go.

I embrace the complexities of my cultural identity and celebrate the fact that I don’t have mine completely figured out. I find it a gift that I can connect with people from both Chinese and American backgrounds. You don’t have to subscribe to a single cultural identity just because your parents were raised in that culture or it’s an aspect of your hometown. Embrace the in-betweenness and uncertainties of your identity. Challenge the ways in which you previously have identified yourself. Dig deeper to find out why you define yourself the way you do. These types of questions and answers won’t come to you overnight… unless you scroll to an Instagram Reel that changes your outlook. Thanks for that, Vivienne.

Contact Anna Beatty at beatty@oxy.edu

![]()