Marilyn Monroe once said, “Hollywood is a place where they’ll pay you a thousand dollars for a kiss and 50 cents for your soul.” It’s only appropriate that the screen siren is the subject of a film that partakes in such tawdrily sourced soul-bearing. Since her untimely death in 1962, Monroe has been fixed as the poster child for Hollywood exploitation and tragedy — a doomed deity of cultural desire.

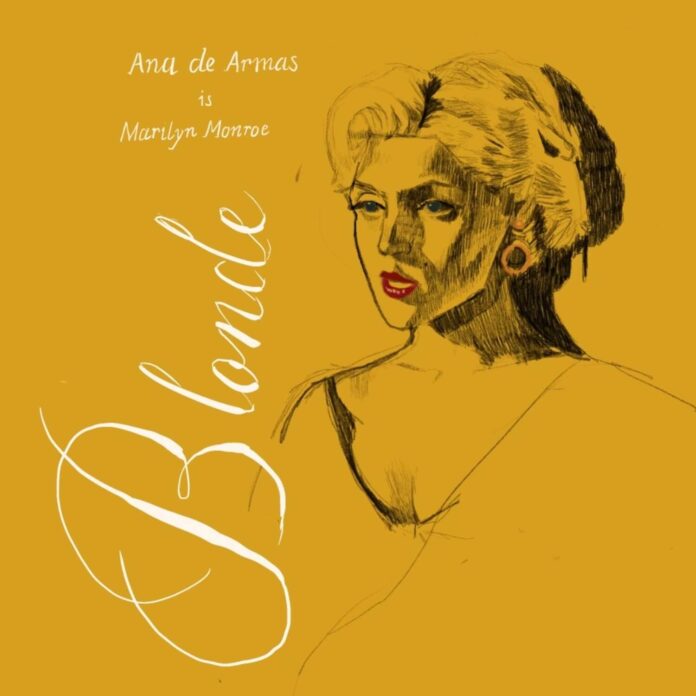

“Blonde,” the newest film by writer-director Andrew Dominik, drives these ideas down our throats with such fervor that viewers must succumb to its mania at some point. And yet, against my better judgment, I must say I loved it. I sat slack-jawed and deeply enraptured, driven to a new state of disbelief at every turn.

The plot sputters forwards with its own internal logic, but the basic conceit is this: Norma Jean (Lily Fisher) leads a childhood of neglect and abuse, albeit one illuminated by the promise of her absent father. As an adult (Ana de Armas, picking up where Fisher left off) she dawns platinum locks and the Monroe moniker, finding enormous success as a fixture of the silver screen. Haunted by her past, she seeks parental love from the men in her life — or so the story goes in this particular telling. Deprived of autonomy and made into an object of mass consumption, Monroe begins to unravel, turning to a dependence on drugs and alcohol that will eventually lead to her death.

Based on the novel “Blonde” by Joyce Carol Oates, this film takes a number of liberties on Monroe’s life. It is decidedly more interested in the allegorical than the autobiographical. Although, I would argue that the problem with this film is not its fictitious verve. The problem is this film’s insistence on punishing Monroe at every turn, augmenting her life into a kaleidoscope of trauma porn. This masochistic storytelling is at times effective in framing her story as a modern parable, but more often than not it serves to deny its subject of any sense of self-fulfillment.

When Dominik presents a recreation of “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” the camera pans to Marilyn, bemoaning the self-sacrifice she made to achieve this career stride — reducing the electrifying technicolor sequence. Dominik, in his surly, straight male voyeurism, seems to have no interest in celebrating Marilyn’s achievements, only wallowing in the misery that lurks beneath the surface.

However, the film is frankly fabulous in spite of itself. The aesthetically inclined will fawn over the perverse glamor of it all, even if that is entirely besides the point. The moments that linger on de Armas’ bejeweled Marilyn drag — perfectly quaffed and ablaze in Old Hollywood glory — are an arthouse homosexual’s paradise. This movie is made to be loved by gay men precisely because it wasn’t; it is camp in the original Susan Sontag form.

Dominik has an eye for dynamic visuals and takes great pains to externalize the cinematic form he is depicting. There are moments of surrealism that are oddly satisfying: in one instance Monroe is participating in a threesome and the intertwining bodies become indistinguishable wavelengths of movement. The bodies proceed to become a waterfall, which reveals itself to be a still from a trailer that she is watching in a theater.

There is something psychedelic about these relentless visuals, even if they sometimes read as overtly film school. The film understands Monroe’s subversive visual power and our relationship to it as an audience.

The main Monroe actress in this film, de Armas, gives such an alarming, full-bodied performance that it transcends the animatronic-style impersonation we so often see in biopics.

Many will hate this movie and I don’t fault them. It is completely offensive, depraved and puzzlingly pro-life in certain areas. But in an era of filmmaking marked by focus-grouped capital interest, one has to admire the audacity Dominik and his players bring to this project.

The film ruminates on some heavy existential thoughts and I was nodding along with them, exhausted into a state of submission. Exasperating yet original, visually dense yet improbably literary, “Blonde” is one of the most infuriating, disturbing and beautiful films of the 21st century.

![]()