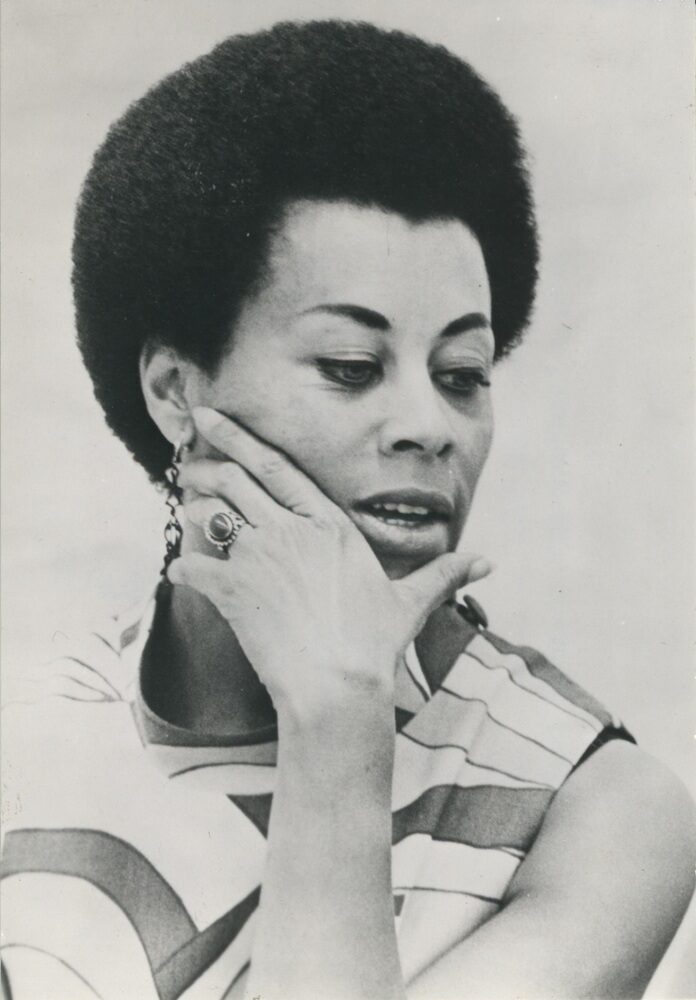

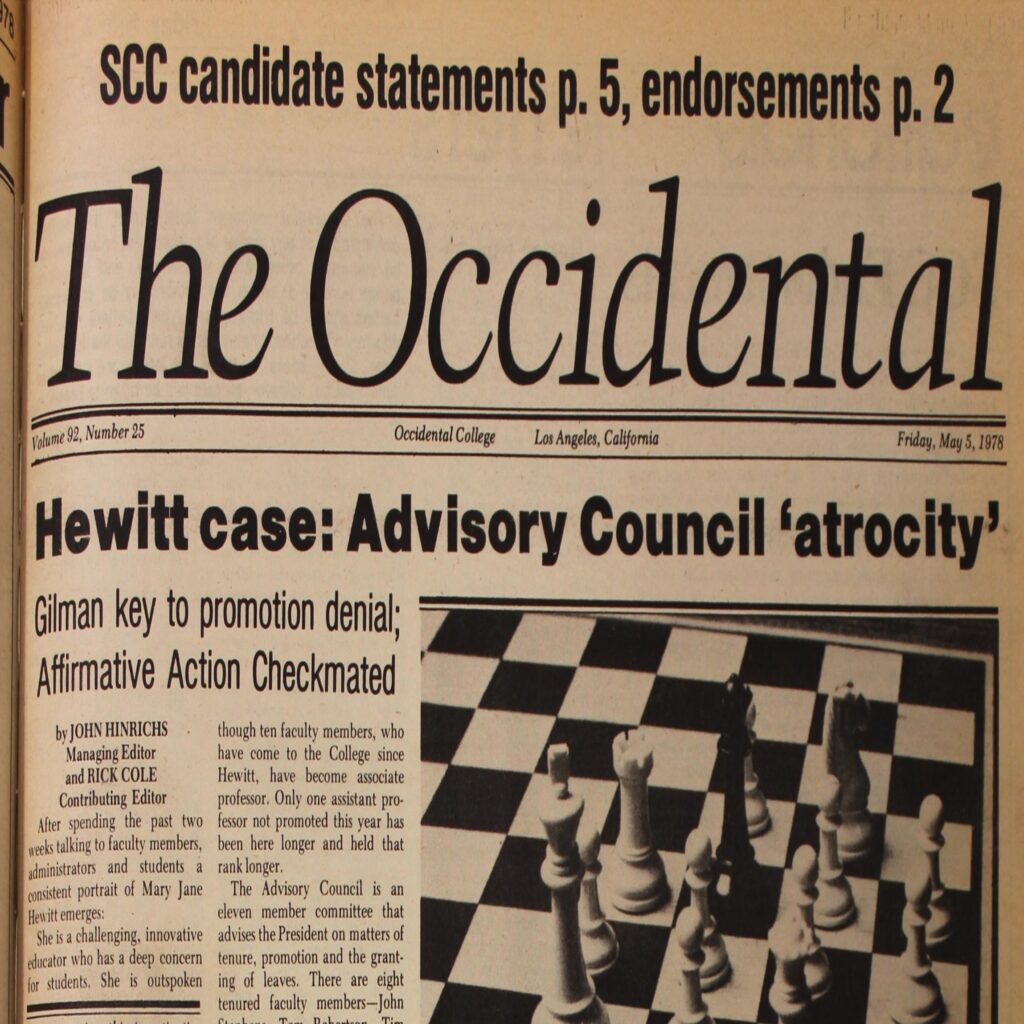

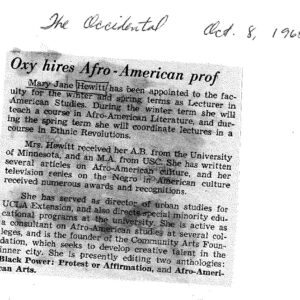

Between 8 and 9 a.m. May 5, 1978, all was quiet on Occidental’s campus as students, faculty members and administrators eagerly read the newspaper, according to the memory of then contributing editor for The Occidental and former mayor of Pasadena, Rick Cole. The Occidental had just released its latest issue with a 10,000-word behemoth cover story, co-written by Cole, on the academic advisory council meetings that had thrice denied a promotion to a beloved American Studies professor, Dr. Mary Jane Hewitt — a scholar of African-American and Caribbean literature and the only Black faculty member at the time. The assertion of institutional racism, to which the article attributed the advisory council’s decision, roused and divided Occidental’s quiet campus, according to Cole.

Occidental announced Jan. 26, 2021 that an anonymous gift of $500,000 will permanently endow the Mary Jane Hewitt Department Chair in Black Studies. Roger Smith ’77, a playwright who was Hewitt’s student and friend, said that for many people who knew Hewitt — or MJ, as she was known to those closest to her — the chairship represents a community triumph decades in the making.

“What this new endowed chair represents to me is the triumphs of student activism,” Smith said. “This is the story not just about MJ Hewitt. It’s about the struggle for the support of this kind of work … and it’s a struggle which just isn’t one woman’s struggle. It’s a whole community, which rallied around her when she was with us and continued to rally for her discipline when she was not with us.”

According to Erica Ball, the professor of Black Studies who will be the inaugural Hewitt Chair, Black people’s diverse struggles and triumphs throughout American history have all been fought by individuals each doing what they can in their own spheres of influence, be it their family, school or community.

“A green place in the city”

Raised in St. Paul, Minnesota, Mary Jane Hewitt arrived at Occidental in 1971 and became popular with Occidental students. Many saw her as a touchstone on campus for students of color, of whom there were extremely few, according to Bob Johnson ’77, her former student.

“Dr. Hewitt was a revelation,” Johnson said via email. “She was warm and engaging, but she also carried herself with this scholarly [artistic] air that I found intoxicating and slightly intimidating.”

In her classes on African-American and Caribbean history and literature, Hewitt was a demanding professor. She assigned ambitious reading lists and had little patience for slacking, according to Kathy Irish ’75, Hewitt’s former student and lifelong friend. She also explored the scholarship of many cultural sources in great depth, rather than just European writers, which was rare.

“There were more than enough occasions where I felt I was holding on to the bumper of a fast-moving vehicle, and just taking the gravel beneath me and taking it in stride because I wanted to be able to benefit from the experience of being in her class,” Irish said. “She had an intellectual ferocity.”

Irish and Hewitt remained close until Hewitt’s passing in 2017, and Irish got married in Hewitt’s home.

“Over time, [Hewitt] became more of a second mother to me. She was always so much of a teacher, a guiding voice, nurturing person. And she was always my professor, as well as a dear, dear person to me,” Irish said.

In the 1950s, Hewitt lived in Paris for a time, where she connected with thinkers and artists from all over the world, according to David Axeen, Hewitt’s former colleague in American Studies and the department’s first faculty member. As part of a close-knit community of Black scholars, she often arranged for musicians and poets to come to campus and meet students. Duke Ellington and James Baldwin were friends of hers; a 1968 video from KQED shows her in conversation with Maya Angelou and community members of Watts, Los Angeles.

“I had an office next door to her and I never knew who I was going to meet,” Axeen said. “She would knock on the door, and she said, ‘David, would you like to meet Abbey Lincoln?’”

Hewitt’s cultural connections contrasted with the curriculum at the time, which Axeen said was informed mainly by a view that the U.S. was an exceptional world power. This was a conviction mirrored throughout the college, according to Alice Duff ’69, another former student of Hewitt.

“We were required to take a class then that was called ‘The History of Civilization,’ and the history of civilization that was taught was essentially European civilization,” Duff said. “There was nothing about any contribution that a person of color made in that. … How can the whole school be required to take that class?”

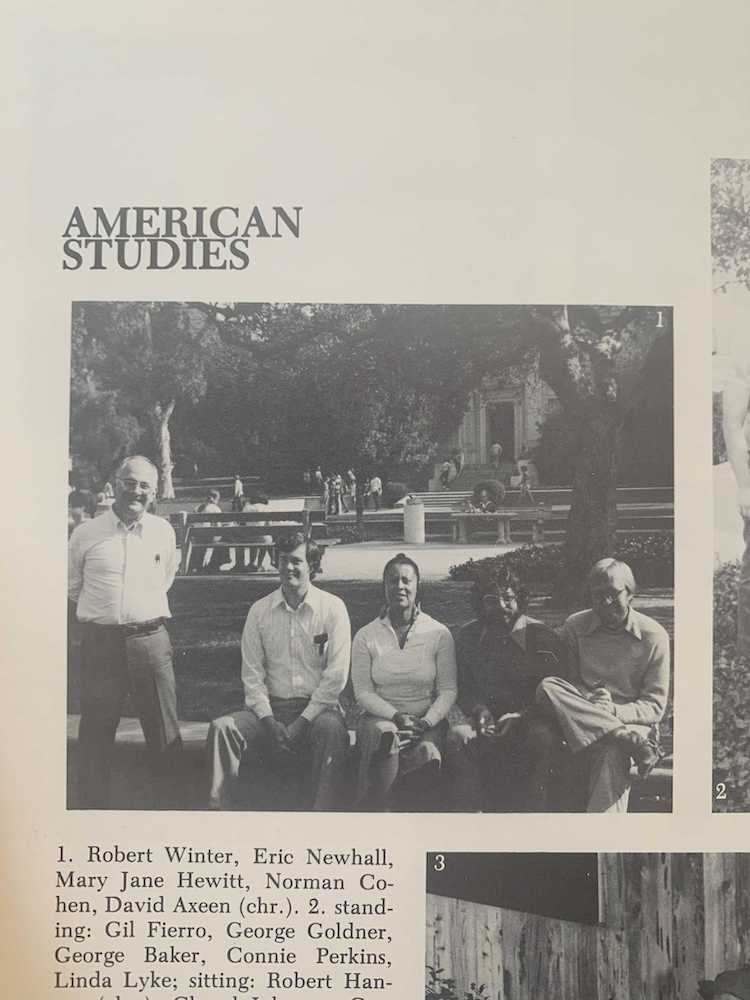

In addition to working to diversify the American Studies curriculum to reflect the reality of American life and cultural experiences worldwide, Axeen also helped lead the push to improve racial representation and gender parity among the faculty; he estimated there were maybe five or eight women out of a faculty of over 100. That number decreased by one when Hewitt resigned in 1978. The lack of legitimacy ascribed to Hewitt and her scholarship — which was intimately tied to the realities of people in poverty, Black people and people beyond the U.S. and Europe — was a symptom of this ingrained ethnocentrism, Cole said.

Cole remembers being surprised when Hewitt resigned during his senior year. Interviewing her for The Occidental, he said he was intrigued by the dignified way she spoke about her resignation, never divulging her reason for leaving or assigning blame to anyone. Cole and John Hinrichs ’78, the newspaper’s managing editor, set out to understand what had happened. What followed was a dramatic series of events that threw Occidental’s racial climate into greater relief.

Cole and Hinrichs had a friend who worked in Campus Safety and assisted the campus locksmith; with his help, they obtained the key to administrative records and found the minutes of the advisory council meeting where faculty hirings and promotions were decided.

“It became clear that both years when her name had come up for consideration for promotion, that the committee was inclined to promote her [from assistant to associate professor] after talking through the pluses and minuses,” Cole said.

Cole said President Gilman had subtly pushed back on the idea of promoting Hewitt, never vetoing it outright but raising enough doubts that the rest of the committee was inclined to go along with it. Interviewing advisory council members, Cole and Hinrichs found that a president dissuading the council from a decision multiple times was highly unusual.

“It became clear to us … that this was not a case that ‘Richard Gilman didn’t like Black people.’ This was a case of what we call institutional racism,” Cole said.

According to Cole, Hewitt was held to a different standard than other faculty members, with members of the advisory council questioning the legitimacy of her research and teaching style in a way that was unheard of for white professors. Her lack of a doctorate appeared to factor into the decision, according to the 1978 article, even though few Ph.D. programs existed in her specialty at the time and her contract stated that this would not be a consideration in promotions.

“Her research, which is very important in a faculty decision, was primarily based upon oral histories, because [for] the subjects she was interested in, there weren’t literate people to write about their experiences,” Cole said. “In Occidental’s liberal arts mindset of the time, someone who spends their life writing about Plato and Aristotle is more valuable than someone who is trying to unearth what happened in the slave society in Greece and Rome.”

Cole also said advisory council members questioned whether Hewitt graded Black students with extra leniency. While ultimately nobody concluded this was the case, Cole said the fact that the question came up at all was indicative of institutional racism.

“It’s just hard to imagine how white the school was, but it was just extremely white and extremely exclusive in terms of the pedagogy and the thought,” Duff, Hewitt’s former student, said.

Cole said a broader mindset enabled racism of this nature at Occidental, which was sometimes subtle and often overt. The U.S. in the 1960s and 1970s was in transition, Cole said; while racial and economic disparities were simultaneously becoming more clear, Reagan’s election marked a conservative, anti-affirmative action tide taking hold. In Los Angeles, poverty and racism led to widespread rioting and gang activity. According to Cole, the school attempted to insulate itself from the troubles of the city and its most marginalized residents.

“It was a very academic school, but not a very intellectual school. People studied hard, they cared about grades, they were ambitious to go on to graduate school,” Cole said. “But they didn’t talk about much outside of the classroom, [about] the ideas that they learned. It was ‘Close the book, go have a beer.’”

In contrast with the prevailing ethos at liberal arts colleges today, Cole said activism and change were not familiar concepts to most of the student body, many of whom saw college as simply another step on a laid-out journey to a comfortable white-collar career. This was mirrored in the leadership of the school as well.

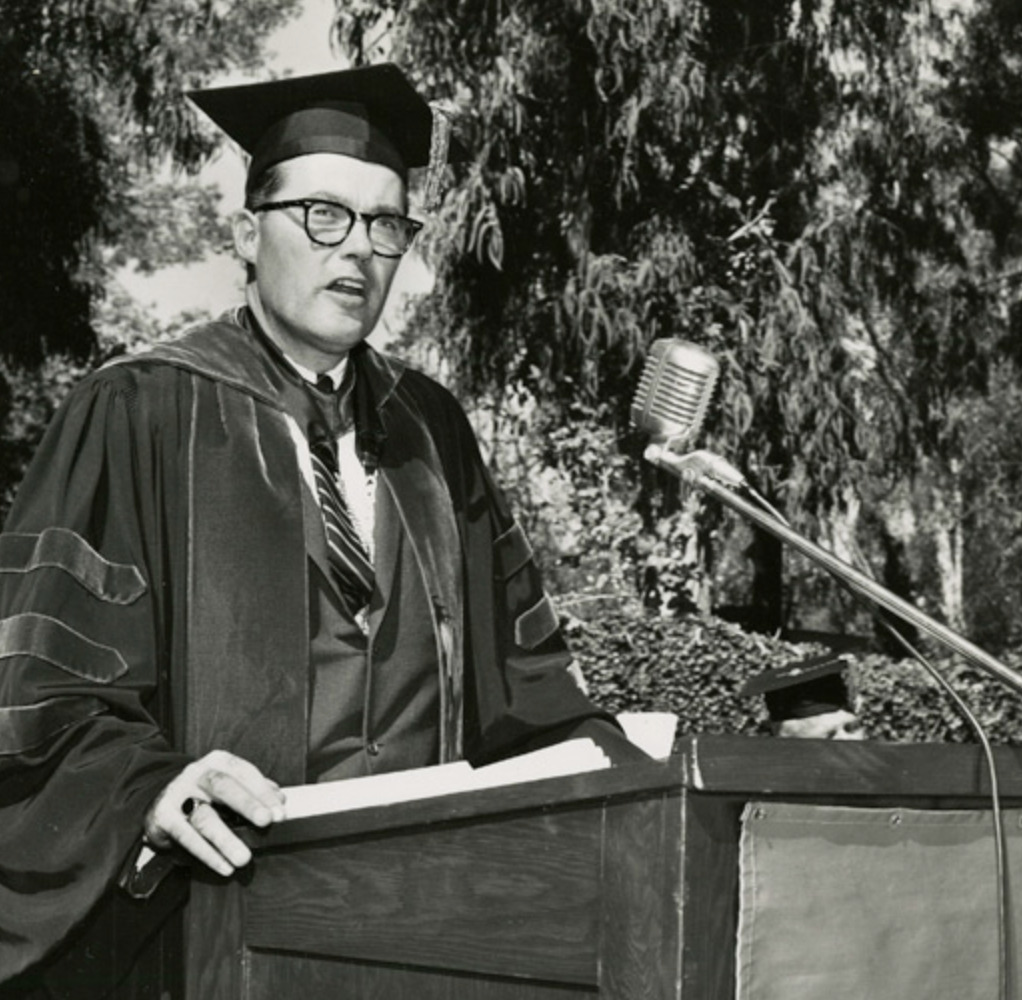

“Richard Gilman had come to Occidental from the East Coast. He was very proudly a Dartmouth graduate — I think he had Dartmouth license plates instead of an Oxy license plate on his college-provided Mercedes Benz,” Cole said. “His motto for the school was ‘Occidental is a green place in the city.’ Cities were falling apart. Where you want to live is in the green suburbs.”

With other liberal arts colleges situated in bucolic locations in the rural Northeast, Occidental’s urban location was considered something to be ignored, an enclave from the gritty outside world, according to Axeen.

“The college catalog used to describe the college as being located in ‘A neighborhood between Pasadena and Glendale.’ It didn’t even mention that it was in the city of Los Angeles,” Axeen said. “We wanted people to think we were just down the road from Pomona.”

The publication of Cole and Hinrichs’ article sparked an outcry from the community as well as disciplinary action for wrongfully obtaining

the minutes. The American Civil Liberties Union volunteered to defend the writers in the honor board trial and students wrote impassioned editorials interrogating the college’s “ivory power.” But through all it, Hewitt herself maintained poise, not wanting to martyr herself, Cole said.

“I don’t owe them anything, and clearly they feel they don’t owe [me] anything, except my salary until I leave,” Hewitt said about the college administration in the 1978 article.

Cole’s disciplinary penalty amounted to a slap on the wrist, he said, and Gilman soon recovered from the temporary blow to his reputation. It seemed the greatest loss was to the many Black students to whom Hewitt was a pillar.

“She was my guiding light,” Smith said.

“In fits and starts”

Black Occidental graduates of 1977 and 2015 alike described an environment where they had to fight for safety, respect and visibility. Irish estimated that out of the 28 Black students in her class, four received their degrees.

“We were advised by upperclassmen, don’t go to Glendale or Burbank and stay out of San Marino (South Pasadena),” Johnson said via email. “Glendale and Burbank in particular had reputations of being Klan strongholds and we were advised that whatever you do, don’t get caught there after dark.”

Johnson also described being detained by the Los Angeles police, who drew guns on him and three other Black students as they drove down a street to drop off a term paper at Hewitt’s home. Irish said her friend’s car window was shot as he was driving and that Occidental never warned her that Black students could not safely travel alone in the area.

Irish, who grew up in an integrated community and attended a racially and economically diverse high school, said she struggled at various points both to relate to other Black students, many of whom had grown up in segregated communities, and to live with the racist attitudes of her white peers.

“I remember my first day, paying my tuition fees, I’m standing in line at the bursar’s window, and this white student behind me taps me on the shoulder and he says, ‘The financial aid line is over there,’” Irish said.

Even while struggling for the most basic freedoms — Duff said there was nowhere off campus where Black students could live — students still managed to organize and fight, doing what they could to reduce the stark inequities they lived with. She recalled picketing a local barbershop that sent a Black student away.

“When I was a freshman, we started the Black Student Caucus,” Duff said. “It’s hard to imagine now how complete the anti-Blackness was. That’s what started the Black Student Caucus.”

Among the demands of the caucus was for Mary Jane Hewitt to be hired in a broader effort to diversify the curriculum to accurately reflect the contributions of societies of color.

“We continued to press our demands. And at the end of my sophomore year we sat in the president’s office,” Duff said. “And anyway, we got a Black Studies class.”

The fight for this progress was a community effort. Duff said the father of one of her classmates, Jini Medina Kilgore, was a highly respected civil rights pastor in Los Angeles, who worked with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Reverend Kilgore spoke with administrators at Occidental to encourage them to look upon the protests positively.

The difficulties of demanding change could not be forgotten, however. Duff said most of the students in the caucus were receiving financial aid and worried their scholarships or even admission would be revoked. This is how change was made, with progress and setbacks, victories and anxieties.

“I think the substantial progress comes because people continue to push over a long period of time,” Duff said. “Now that Black Studies is now a major, and that we have 13 black faculty, and that there’s an endowed chair … That’s wonderful. I think the progress has been slow. I would like to say steady but I don’t think it’s been steady. It’s been in fits and starts.”

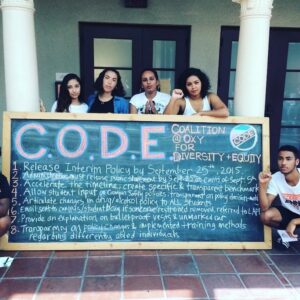

Decades later, in 2015, Nina Reynoso ’16 and Antoniqua Roberson ’16 were among the students who organized a walkout and occupation of the administrative building. Reynoso said Black students felt not only that they were not being listened to, but also that they were at times being actively silenced.

“A fraternity on campus planned on doing an ISIS Malaysian Airlines Ebola party,” Reynoso, a doctoral candidate and professor at UCLA, said. “It was on Facebook [with] all of these memes, like ‘Come as your sexiest Ebola nurse.’”

Reynoso went to the Dean of Students, who said that because the fraternity house was off campus, the school could not do anything about the party. She cited this as among the many reasons she felt compelled to organize for equity at Occidental through Oxy United for Black Liberation (OUBL).

Reynoso said she immediately felt a rush of energy from the walkout, when students dressed in black and left their classrooms together to mark the start of the occupation.

“I think for a lot of us who organize it feels very gratifying to feel like, ‘This is my medium to actually be heard,’” Reynoso said.

During the Occupation, some students who had contacts in the media arranged to invite press coverage, others worked to secure donations for occupiers’ food and water and still others did clean-up duty so Occidental’s facilities workers would not have additional work.

This solidarity, too, came in fits and starts, according to Roberson.

“We had plenty of students of color that weren’t in favor of the Occupation, that weren’t in favor of the radical organizing that we were doing,” Roberson said. “So that was also a challenge [at] a predominately white institution, where students of color are already the minority and then within that small population of students of color, organizing, there’s an even smaller population of students that are in favor of the organizing that’s going on.”

Roberson described an incident when the Black Student Alliance (BSA) set out a bag of Skittles and a can of Arizona Ice Tea as a memorial for Trayvon Martin, who was holding those snacks when he was killed by the police. Students at Occidental vandalized the memorial, ate the candy and drank the ice tea. The BSA filed a complaint against those students, who proceeded to file a retaliatory complaint against the entire BSA, according to Roberson.

On the day of the hearing, members of the BSA used its organizing powers to show their camaraderie.

“All of our Black Student Alliance members, including Black students, other students of color, white students, allies … all of us attended the hearing,” Roberson said. “And if you could have seen that little tiny room that they had us and we had students in the hallway, students sitting on desks, students sitting on the floor!”

Even as the nature and appearance of racism changed between the 1960s and 2015, there was much in common between these alumni’s stories: the feeling of tokenization, the exhilaration of solidarity, the worry of first-generation students not being able to walk across the stage, the moment of decision to seek change. According to Reynoso, Black Studies can provide a grounding for these varied yet shared experiences.

“My students, particularly my Black students when they come to office hours, time and time again what they tell me is, Black Studies provides them the language or discourse to talk about things that they’ve already known,” Reynoso said.

“The Black radical tradition”

Talk of a Black Studies major at Occidental was underway even before 2015 when OUBL listed the creation of a Black Studies department as one of its demands. In Spring 2018, the faculty voted to approve an interdisciplinary Black Studies program consisting of classes from several other departments, according to Wendy Sternberg, Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of the College.

“When we add a new program, we don’t necessarily have new resources fall from the sky that can support it,” Sternberg said via email.

The lack of funding and full-time faculty became a point of contention as Courtney Baker, a co-founder of the Black Studies program, resigned in April 2019, listing several needs for the program to thrive, including departmental status and compensation for faculty interdisciplinary labor.

At least three of Baker’s points are now being met. With three new faculty hirings within Black Studies and the endowed chairship, which will generate $25,000 per year while leaving the principal untouched, Black Studies is finally becoming a department, according to Sternberg.

“It’s great for the department in terms of allowing the department to be able to do more things for students: funding, speakers or other initiatives,” Ball said. “Secondly, it really signifies institutional support for the department. And that’s fantastic. If we look at the history of Black Studies or African American studies or Africana studies at [predominantly white institutions], the story hasn’t always been one of strong institutional support.”

Baker expressed delight that Ball and the department were recipients of this gift, and that the discipline of Black Studies now has a more permanent foothold at Occidental.

“I admire Dr. Ball tremendously, and I know from working with her that she is wholly deserving. Quite simply, there would be no Black Studies curriculum at Occidental without Dr. Ball,” Baker said via email. “She is not only a tremendous scholar of Black studies and of African American history, she is also an extraordinarily adept administrator. I learned a great deal from working with her, and I carry those lessons with me.”

For Esther Karpilow (junior), a Black Studies major, these classes have provided a much more substantive dig into Black history than she got from her high school AP U.S. History class.

“The level of information that I gained about history and my understanding of the U.S., the world in which I’m living currently, moving about the world as a Black person, it completely gave me a 180,” Karpilow said. “The environment in the class is unlike really any other class. It’s like a level of realness that I’ve never experienced in another class.”

Karpilow said she also appreciates the rare class in which she is not the only Black student, or one of very few, although she clarified that even most of her Black Studies classes are not necessarily majority Black, or even half.

“There have been some uncomfortable moments but I feel the discomfort is a good thing. It’s necessary, because it tends to be coming from white folks in the classes, and I feel like there are not many spaces in which white people are pushed to that level of discomfort,” Karpilow said. “The realness is somewhat related to the discomfort.”

The range, realness and variety of subjects discussed in this curriculum exists because the field itself is drawing upon over a century’s worth of intellectual inquiry, according to James Ford III, a professor in the English and Black Studies departments.

“A major milestone in the history of Black Studies pops up in the 1960s but actually Black Studies has been around in the United States since the 1890s,” Ford said. “The department takes it seriously that Blackness refers to a global collective consciousness, a global set of complex experiences and it refers to a diaspora that’s still looking for ways to define itself in an open-ended way, not not closed off based on one single definition or theory.”

Ford said the diversity within the African diaspora is what excites him most, and that each Black Studies tradition can provide a wide array of lenses for understanding the racial and economic crises that rocked this pandemic year, as well as strategies for coming out of it closer and stronger as a society.

“Teaching and studying the history of black folks … I think of it as a long freedom struggle and one that involves many different kinds of activism,” Ball said. “So, if you’re looking for a playbook from history to show you the various ways that people banded together to fight for positive change, African American History is a great place to look.”

This field has not always been treated as a valid area of scholarship. Ball said a colleague at her first tenure track job, upon hearing that Ball studied 19th century African American history at the City University of New York Graduate Center, told her she was “almost legitimate.”

“That was a painful moment for me, to have a colleague be so bluntly dismissive and disrespectful. At the same time, however, I feel entitled to do the work that I do, and go where I want to go and be who I want to be,” Ball said. “I do that proudly as an African American woman, I represent myself and I represent my family. We have a long line of people who have done great stuff that’s just unsung and unheard of. And I’m happy to be here continuing the work.”

Ball said she had ancestors who were enslaved and brought from Maryland to the Florida Panhandle. When they were emancipated after the Civil War, they scraped together enough money to buy a tract of land, some of which they used to build a family home, and some of which they donated to the community as an African Methodist Episcopal church. One of them even wrote to the American Missionary Association to request that a Black teacher come to their town to start a Black school.

“These are not wealthy people. They’re regular folks, and they exemplify this kind of determination to build a community and to work together, and that gives me enormous pride,” Ball said.

Working cooperatively, stitching together change piece by piece, has always been the story of Black studies and its most enduring throughline, according to Ball.

“That’s part of [the Black radical tradition],” Reynoso said. “Knowing that the work is never done. But that the piece that you do is sufficient.”

![]()