Three-quarters of college students reported moderate or severe distress between 2020 and 2021. Sixty percent of students during that same period met the criteria for at least one mental health issue. Sixty-one percent of Americans ages 18–25 reported experiencing loneliness frequently, or almost all the time. The statistics vary depending on the study, the year and the specific questions posed. But many Occidental students do not need to see the numbers to feel their weight. We see it in the waitlists at Emmons, the anonymous revelations on Oxy Confessions. When we ask someone on the Quad how they are doing, “tired” is a frequent answer.

“Everyone’s so tired,” Koi Fuziyi Smith (junior) said.

Vivian Garay Santiago, the assistant vice president for student affairs and associate dean of students, said she works personally with struggling students, both to support their well-being and to help them stay on track with their academics. She said colleges nationwide are noting dramatic increases in mental health issues among their students, and Occidental students are no exception.

“We were already seeing a rise in anxiety and depression issues prior to COVID, but since we returned to in-person learning, these issues have risen along with other severe and acute mental health issues,” Santiago said via email.

These issues are playing out in many domains of students’ lives, including academics, according to Santiago. She said faculty members are noticing that more students are struggling. This is reflected in Care Reports, a tool used for community members to refer a student to the Dean of Students office for more support. According to Santiago, the number of Care Reports submitted by faculty has doubled from five years ago.

“Back when I started at Oxy, the majority of Care Reports were submitted by the Residence Life staff, but now faculty are by far the most frequent reporters,” Santiago said via email. “Last academic year, Care Reports submitted by faculty exceeded the next category of reporters by approximately 20 percent, which reflects a dramatic change in who used to submit Care Reports.”

Santiago also said that a newer phenomenon her team is noticing is that more students are “ghosting” their academic lives.

“We received many reports of students who just stopped attending class and responding to faculty altogether,” Santiago said. “When we would reach out to make sure they were okay, they were also very reluctant to respond to our staff; however, we could see that they were living on campus and eating in the dining facilities.”

Nobody knows exactly why these trends are occurring, but everybody interviewed for this article had some ideas. The pandemic, unsurprisingly, and the deep isolation it created. Violence against marginalized communities, and uncertainty on how to process a constancy of disturbing news. Social media and the Internet. The cost and inaccessibility of therapy services. An expectation to work continually — the resulting lack of sleep.

Adam Cole (junior), president of the Associated Students of Occidental College (ASOC), said he believes the pandemic is the main contributor to the trend. Cole, along with Emmons Wellness Center, advocated for professors and other leaders on campus, as well as students, to undergo a training called Kognito starting last semester. Cole said the goal of this training was to empower people to use their positions on campus to notice those who are struggling and intervene, directing them to resources on campus.

Cole said he thinks that many of the mental health issues evident now are because students fell behind and are struggling to raise themselves back to the expectations that Occidental sets.

Santiago said the semesters of remote work might have gotten students into habits of avoiding in-person opportunities for engagement or checking out mentally. And Cole said some professors are eager to raise the standards with stricter policies on late assignments and attendance, worrying that students might take advantage of flexibility.

“When we talk about mental health, we talk about academic flexibility. They’ve come hand in hand throughout the entire conversation,” Cole said. “The balance between accountability and flexibility has not been reached.”

Mia Ellis (sophomore) said she believes that academic anxiety contributes to her mental health difficulties. She described a gradual process last year where she felt more and more distant and spaced out for a few weeks. But then she walked into a class and realized that there was a test that she had not known about. Her anxiety jolted upwards, and she began to cry.

“So I went home and I was like, I think I need to do something about this,” Ellis said.

Ellis said she worries about the future.

“For example, all my advising meetings, right? I’ve cried at every single one of them,” Ellis said. “But definitely [during] midterms exams, or when grades come out, the future suddenly seems like a really big thing.”

The bubble of a liberal arts college does not necessarily insulate students from these challenges, Ellis said.

“Part of it might be that we aren’t here forever. It’s a four-year college; you feel like everything you do here matters for when you’re not in such a little bubble,” Ellis said. “Also, maybe there are a lot of expectations because this is a really pretty campus. And everyone’s so nice. And everyone seems to be having such a good time. Like, oh, my gosh, I need to be having the best time.”

These days, mental health is sometimes compared directly to physical health — after all, you would not expect to heal from a fracture using willpower. Both kinds of health require attention and healing, according to Anna Rivera, a staff psychologist at Emmons.

But the comparison has its limits. Thousands of people do not tend to be individually afflicted with fractures at the same time. And medical advances have improved the outcomes of many physical conditions, but progress has not been as linear for mental health.

Smith, who identifies as a disabled person, said that in disability spaces, people tend to differentiate between a medical and social paradigm of a condition. With so many people struggling with this issue, a social paradigm might also be illuminating. Smith said he saw an Instagram post applying this to mental health, which stuck with him.

“Mental health crises that are happening right now can’t be solved by therapy, or medicine or things like that,” Smith said. “What it’s showing is not that the people are sick, but that the society is sick.”

According to Rivera, our society’s pervasive capitalistic culture is one symptom of this sickness.

“It tricks us into believing that we need to do, do, do in order to be ‘successful,’ and doesn’t allow time to actually be — slow down, explore our own values and needs, and connect to others in meaningful ways,” Rivera said via email.

If someone is in an unsafe environment or living situation, it is also unrealistic to expect them to slow down and reflect in this manner, according to Rivera.

“When basic needs like food, water, shelter and safety are not met, that becomes the focus of our energies, and our ability to connect greatly suffers,” Rivera said.

Smith said he is interested in thinking and learning about intergenerational trauma: the complex sets of ways that the effects of historical events are passed down through a family. He said he can see how both sides of his family have struggled to overcome the systemic hardships imposed upon them, and the effects are still being felt.

“That’s in my DNA. I feel it in the way my family interacts,” Smith said. “And that affects me. When sad people are interacting with sad people, you sort of keep each other [that way].”

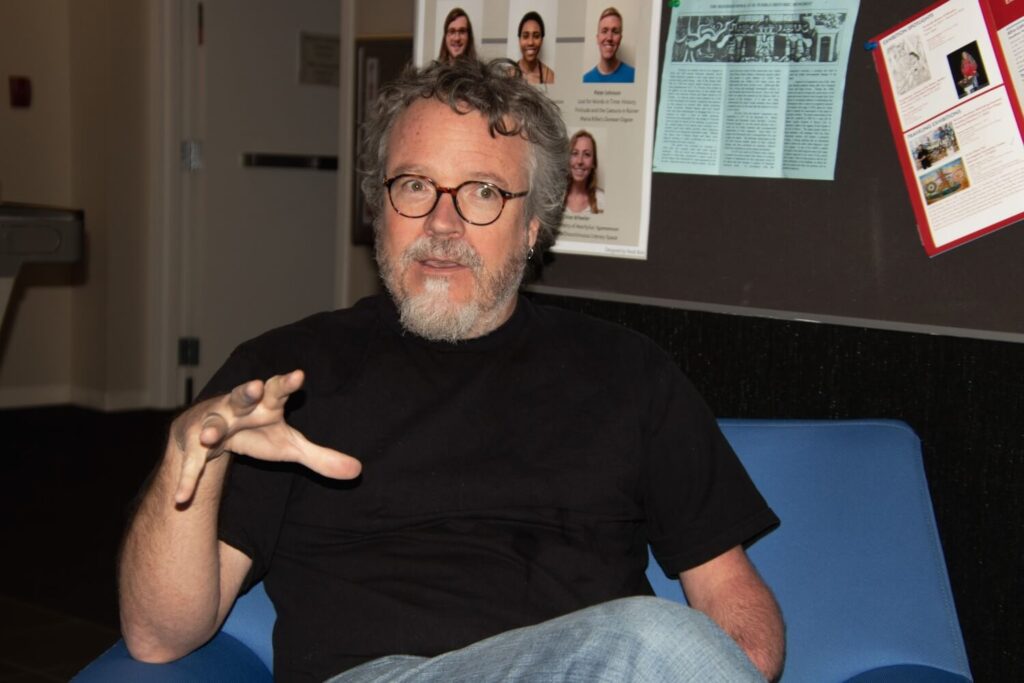

Jacob Mackey, professor of Comparative Studies in Literature & Culture (CSLC), believes institutional narratives around harm, trauma and microaggressions could be exacerbating the mental health crisis. Mackey, who is missing a limb, said he has faced a lot of aggressions in his time, micro and otherwise. He said he was physically and verbally assaulted regularly throughout his childhood and early 20s, and that microaggressions happen all the time as well.

“Everything from people holding doors for me, because they think I can’t open the door, to being amazed that I can tie my shoes,” Mackey said.

He described an incident when a student came up to him on the last day of class, full of praise.

“[She said], ‘I just want to say, I’m so impressed.’ And I was getting more and more excited. I can’t wait to hear. [Then she said] ‘I’m so impressed by the way you can hold a book,’” Mackey said. “And it’s like, wait, we just did a whole semester. And I taught you Latin.”

Despite how acutely he has been made aware of the prejudices of those around him, Mackey said he never thought of them as causing lasting damage or trauma.

“No one ever told me, and I never thought, that they could do me significant harm,” Mackey said. “I thought they were annoying. And I wished people would be more sensitive.”

Mackey said he receives emails from Occidental’s administration that advise faculty members to remain vigilant about all forms of bias. He said what surprised him the most about a recent email was that it said microaggressions can cause lasting harm whether they are intentional or not.

“I think it’s no wonder that students are walking around with a sense of malaise because they have the administration telling them 24 hours a day that everything in their environment is a potential significant harm to them,” Mackey said. “We are suggestible beings, and when people tell you that your environment is full of hidden harms that are just waiting to damage you, [we] become less open to the world and more leery about our environments and less trusting of one another, less trusting of one another’s good intentions.”

Mackey said there is not just one way of viewing these incidents, or even of viewing genuinely horrific world events, like mass shootings. He said communications from the administration in the wake of such events tend to assume that students are uniformly traumatized by them, which he said is a monolithic understanding of the world.

“Like, maybe some people hadn’t even heard the news, maybe someone had managed to take a perspective where they weren’t totally broken by it, but you’re telling them that the authentic response is to be broken by this news,” Mackey said. “Then you wonder why more and more students show up at Emmons saying, ‘I’m broken by what’s going on.’”

Mackey, who specializes in Latin and Greek languages and literature, is teaching a class this semester called Beyond Resentment: the Literature of Life Affirmation from Ancient Rome to the American Blues. He said the philosophers the class discusses offer alternative ways of considering our relationships with one another: ways that can make us feel happier and more whole. Part of that is recognizing that when we come into our interactions with other people, we all might — or probably will — impose on others, just as they do on us.

“The stuff we’re reading sort of says, ‘Look, the social world is what it is, people are what they are … You’re gonna meet people who are jealous. You’re gonna meet people who are trying to take advantage of you. You’re gonna meet people who are insulting to you,’” Mackey said. “And what we have to try to do is actually see more of ourselves in them, and more of them in us, if you will, and recognize that we’re all brothers and sisters ultimately.”

Despite how overwhelming some struggles can be, many people spoke about small shifts — actions, ways of thinking — we can take to reclaim some agency against the forces of this world. Rivera emphasized the importance of leaning on those around us, and on nature, while Smith said he is trying to get into a good sleep routine.

Santiago said students should commit to taking small actions for their well-being. While it is easier said than done, she said, it would be a step in the right direction for students to show up to their classes or respond to emails from faculty and staff, for example.

“If students could make a commitment to themselves not to isolate to such a degree that they stop responding to this kind of outreach, that would be a great step,” Santiago said via email. “Reaching out for help when problems emerge and before the problems become debilitating is really important.”

The world is alive and ever-changing: some of it deeply good, some devastating, most of it out of our control. All of us, and everyone we’ve ever met, will eventually lose the things and people that are most precious to us, Mackey said.

“What do we do in the face of that fact? One option is to descend into depression and misery about it and bemoan it,” Mackey said. “The other option is to say, ‘Wow, I am so grateful for this moment that I have been given, like what a miracle that I’ve been granted this moment.’ And, in fact, its very brevity makes it that much more precious.”

Gratitude does not always seem intuitive or even reasonable. It can be easy to get off track, Mackey said.

“You have a choice, which one you pick,” Mackey said. “And you need to be reminded that you have a choice.”

Contact Divya Prakash at dprakash@oxy.edu

![]()

[…] Everyone’s talking about mental health on campuses and ‘Oxy is no exception’By Divya PrakashThe Occidental,Occidental College […]