As I write these words down, it is the 15th anniversary of 9/11. Today is also Eid al-Adha, one of the holiest days in the Islamic Faith, which I abide by as both a familial and personal decision. And today, I find myself struggling to form words that would effectively articulate the implications of my personhood.

Today, I ruminate on what it means to be Muslim in America; I consider what it means to have spent near-precisely three-quarters of my life in Post-9/11 American Society. I debate with myself about what it means to integrate the cultural values of my religion, the society I have grown up in and that I have had the invaluable privilege of learning from my parents — of how to synthesize these things in perfect harmony I am truly without answer.

I suppose I should say that I am not on a search for answers concerning what it means to be a (half) (white-looking/white-passing) Arab Muslim in Post-9/11 America. I am not writing to articulate America as a singular, evil, militaristic force that is responsible for disproportionate targeting and intolerance of its marginalized minorities — although I certainly argue there is significant merit in these aspects of this statement. Rather I have come to understand that my existence as a member of American society is mediated first and foremost by 9/11.

9/11 was, is, and will continue to be an irrevocable tragedy, but by no means should it be regarded as a cataclysm — in no way is it an isolated event, nor does it serve as genesis or denouement. It is a tragedy, as is the violence, turmoil and destruction that both led to it and happened in its wake on and off American soil. But I think we must put the latter of those two concepts into the spotlight, and consider where our individual values are. What has produced our individual and cultural sentiments surrounding the event, what are our own connections to these events and how do we mediate the identities we have accumulated over the courses of our lives? We cannot regard it as a standalone moment in history, for doing so surely invites its repetition. It is on all of us to be critical in our observations and understand how the world around us is a product of past actions, and understand the future that will become reality if we repeat the same patterns. I know in my heart I would be remiss not to say that the innumerable casualties of war should never be compared; this is about memorializing all lost to the violent systems we live in and around, American or otherwise. This is about understanding our intersecting, multifaceted connections to and responsibilities for all violences and injustices.

This is about fixing our tomorrows because our todays are so plagued by our yesterdays.

Last week on my campus, our resident Republican Club elected to memorialize that tragic day with the placement of American flags in the central area of campus. Some of my fellow students (whom I consider friends) decided to take down those flags and put up alternative memorials that honor both the victims of the attacks on American soil, and the victims of the repercussions of those attacks. In the same way we call each other to action to memorialize the fallen on this day every year, we should be inviting one another to work to embrace differences and build communities where we may all thrive; we must work towards the equality few of us have ever truly been granted. We must convoke one another to objectively recognize how aspects of this memorial elicit visceral reactions for innumerable individuals and groups. Immediately jumping to critique either group’s initial desire and their frames of reference is foolish, especially when critiquing the students who chose to alter the memorial last night.

After the tensions had lowered and people had dispersed on the night of the memorial’s defacing, I found myself sitting alone in the quad, surrounded by American flags and an energy of unease. I stayed there a long while, alone, and pondered my place on this campus and outside of it. I’m one of the only Muslim students here, as well as one of the only Arab students. For me, the American flag is a representation of a forced awareness of self. I am conscious of the fact that I have been forced to shape my existence as a response to the American flag, as a response to the potential for intolerance and hatred.

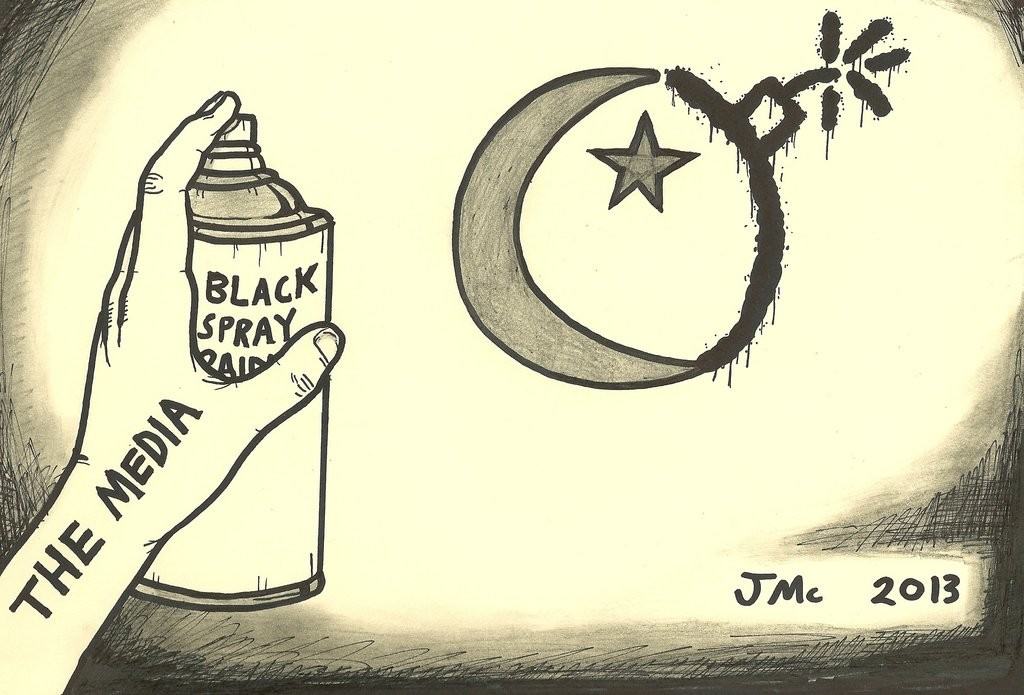

And today I find myself meditating on all of these different thoughts, realities, and emotions specifically because they make me who I am, and they are all produced by who I have been — often, who I have had to be. I have grown up in a society of surveillance, fear, intolerance and awareness. I have grown up a Muslim, and now understand that this is no longer a religious statement but a political one. Being Muslim in America is in and of itself a psychological state that is isolating, that is uncomfortable, that is irreducibly and intrinsically linked to America’s narratives of nationalist pride and militarism. Nearly the whole of my life has been spent under the shadow of the American flag, and three-fourths of it under the looming shadows of the twin towers.

On one of the holiest days in my religion, when I reflect on what it means to sacrifice, I cannot help but synthesize the various factors that have made me who I am. I cannot help but observe how 9/11 has informed this election, and how it has influenced every day of my life whether I consent to its role or not. I think of how much has been sacrificed by so many people for so many causes. I must acknowledge the sacrifices I, my family and people like us have had to make every day since 9/11, along with the ones we made prior to that day. I hope that we may all understand the myriad ways a day like this can allow us to reflect on who we are and the communities we seek to manifest. And I should hope that one day the sentiments I have after 15 years of this reality — the fears, the frustrations, the sadnesses, the confusions — are no longer relevant.

To inhabit the space I do — somewhere in between the worlds of my friends, colleagues, peers, professors, and so on — is something of a calm and accustomed loneliness. I’m not sad about it and you shouldn’t be either. But I think it’s important to know that I have come to feel this way because of the world I live in — the world we live in.

Addendum: Since I started writing this, I have repeatedly been subjected to comments, stares, unwanted attention and assumptions. Allow me to elucidate something: I had nothing to do with the adjustment of the memorial. To assume I did, for whatever reason and especially the unbelievably racist and harmful ones, speaks to our failure to manifest a culture, and a community, of care and consideration.

![]()

So your friends “altered” the original memorial? Your euphemistic language gives you away. Face it–they vandalized the memorial. To promote their counter-view, they actually had the opportunity to produce their own separate memorial and put their argument fairly before the students, but instead they simply chose to destroy one that they didn’t like, and in so doing claimed the right to decide what their fellow students get to see.

Freedom of speech as guaranteed by the Constitution is not subject to moral relativism, and the act of uprooting and throwing flags in the garbage can’t be justified simply because its politics were correct in the minds of you and those who think likewise. As for the embracing of differences that you claim to advocate, please understand that the students’ act of “altering” the original, flag-based memorial was the perfect opposite of that. It was an attempt to silence and negate a view different than their own.

It’s rather interesting you bring up moral relativism and then attempt to conflate your opinion with “fact”.

Rather, consider the memorial in concept: examine the idea of a memorial versus the idea’s manifestation; examine how we are all taking positions on this issue and how your position has no less of a nod to a sense of moral relativism.

Regardless, I didn’t claim and do not claim to exclusively support the altering of the memorial. Instead I argue that this is an opportunity for all parties involved in any way to consider their position and work towards understanding. Had you considered my opinion objectively you would recognize this.

Lastly, I don’t speak for the people who did it, and neither should anyone else.

Calm down. Elsewhere the author also wrote the following:

“After the tensions had lowered and people had dispersed on the night of the memorial’s defacing,”

So while it’s nigh on impossible for someone as knee-jerk prejudiced as you to have empathy you might instead at least stop being a bully. Maybe having a Thesaurus handy would help you diffuse some anger. They’re free on-line.

“Prejudiced….” How is arguing for equal freedom of speech for everyone any evidence of prejudice? Please explain. (A serious question.)

As for “empathy”…the same question applies.

“Bully…?” Do you feel bullied by a composed, dissenting opinion made up of civil words and phrases? Really?

Perhaps you’re assuming a stance on my part regarding the topic of the original display (9/11 remembrance), or that of the vandals (issues connected to and stemming from 9/11), and are characterizing me based on that assumption. In fact, I’ve expressed no stance on those topics at all. My comments merely support the free exchange of ideas, and criticize those who would silence opposing ideas, as the flag vandals did.

As for your semantic point–yes, the author also used the word “defacing.” But since the flags weren’t defaced–they were thrown away–it seems that term also serves as a euphemism.