Barbies were banned from my house when I was growing up.

“It’s just a doll,” I pleaded on my seventh birthday as I clutched the plastic figurine, its long, blonde hair tickling the base of my thumb.

But my dad was adamant. The Barbie, with its vacant, pink-lipped smile and unblinking blue eyes, was tucked away into the back corner of his closet — doomed to spend the remainder of its shelf life nestled among old work shirts and paisley ties.

“Don’t you think you’re being a little extreme?” My mom asked later that night.

It was 10 p.m.; I was supposed to be asleep but had woken up to the sound of raised voices in the hallway adjacent to my room.

“Sana’s right,” she continued. “It is only a doll.”

My dad paused. I pressed my ear against the door.

“I don’t want my daughter to think her value lies in her looks,” he said. “I want her to be more than just pretty.”

The truth is, though, that I do not meet the conventional beauty standards that my discarded Barbie embodied. Yet, as I grew, past high school and into college, men still objectified me as if I were a toy — just not an American one. I was “exotic,” a word wielded as a form of dehumanization and control. When you call me “foreign,” you define me by your experiences, not mine.

Growing up, I wasn’t pretty. Instead, I was cute in the way that all elementary school kids are cute, with missing teeth and pigtails affixed with scrunchies and sparkly barrettes. I was awkward in the way that all middle school preteens are awkward, with frizzy bangs and a thick layer of kajal smeared across my waterline. I flew under the radar in high school, secure in my position as an average-looking nerd who read too many books and attended too few parties.

Now, in college, I am different — a word that is meant to be a compliment but only emphasizes all the ways in which I do not measure up to normative standards of beauty.

“Where are you really from?” has become a common refrain — a reference, I’m sure, to my untamed eyebrows and wide-set nose.

“How did your English get so good?” strangers ask, marveling at the subtle lilt of my accent that lingers long after phone conversations with my parents.

“Sana,” they say; my name fizzles flat on their tongues. “How unique! Does it mean anything?”

“But you don’t look Indian.”

“You’re a halfie, right? Pakistani? You must be.”

“So, what are you?”

The constant barrage of questions soon turned grating. I’ve grown tired of the asterisk that attaches itself to my identity whenever I tell people I’m American, the insistent, pervasive belief that I don’t quite belong to the country I consider home.

When I told my mom I was writing this article, she sighed.

“You’re overreacting,” she said. “They just want to get to know you better. You should take it as a compliment.”

I did not take it as a compliment when a boy messaged me on Tinder to tell me, first, that I looked “foreign” and later, for clarification, that I was “beautiful but not white.”

I did not think that stranger wanted to get to know me better when he grabbed me at a club, his eyes roaming my body like it was uncharted terrain he had yet to conquer.

I was not overreacting when I pulled away from his probing inquiries about my ethnicity; I was not defensive just because I told him to mind his own business.

It was not okay that he felt entitled to an answer. It definitely wasn’t okay that he felt entitled to me.

Whatever the intention, these daily intrusions turn me into a papier-mâché art project, assembled out of tissue-thin stereotypes and multi-layered expectations of who I’m supposed to be. “You’re not like most girls,” is not a tribute to my personality but an affirmation of my position as an outsider. Snide remarks about how I “sound too white” do not make me feel included; they make me feel as though I am not enough. Conspiratorial comparisons to “coconuts” only shove me further away from my sense of self.

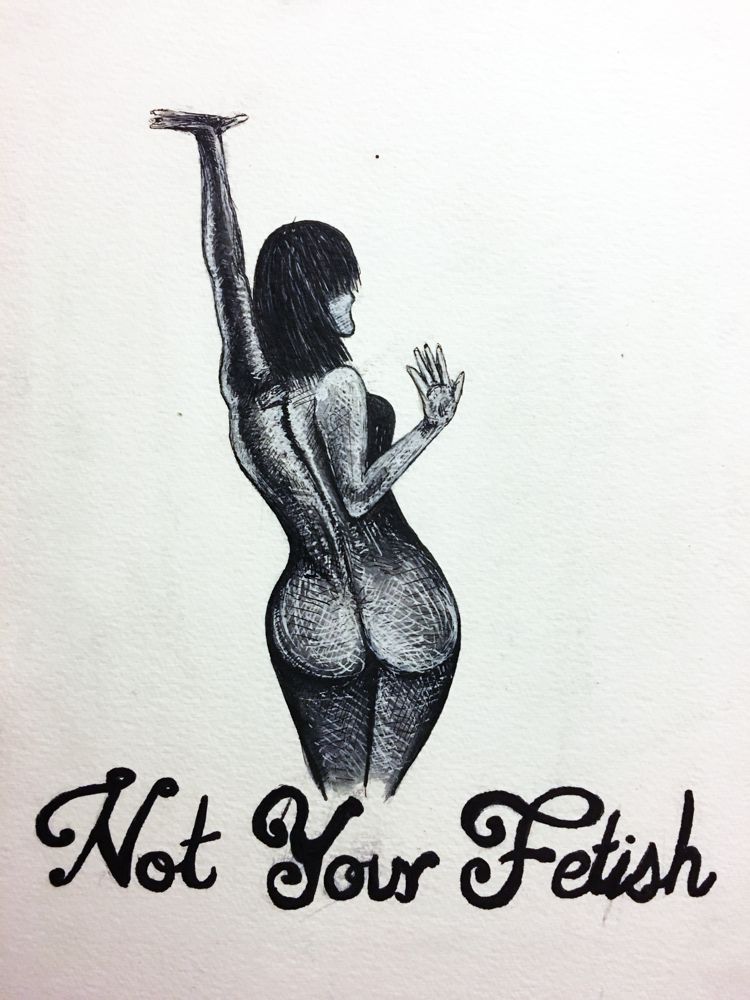

“Exotic” is not, and never will be, a term of endearment. I refuse to be someone else’s doll, my so-called racial ambiguity used to justify the relentless invasion into my personhood.

I may have outgrown Barbie — their blank stares and artificial grins now give me the creeps — but I still have not let go of the desire to be pretty. The difference is that I do not want to be admired because I am “unusual” but because I am me.

So the next time you see me alone at a party, nursing a red solo cup in the corner of a dimly lit room, remember: I am quiet, not because I’m cloaked in an aura of mystery, but because I don’t like talking to jerks.

Sana Vasi is a senior Diplomacy and World Affairs major. She can be reached at vasi@oxy.edu.

![]()