Gentrification has continually been at play in Occidental’s own backyard — in fact, our school has ultimately been complicit in gentrification, sometimes very deliberately.

As the Oxford English Dictionary defines gentrification, this “process of renovating and improving a house or district so that it conforms to middle-class taste” is responsible for the continuation of social inequity. There’s an important sub-definition, too: “the process of making a person or activity more refined or polite.”

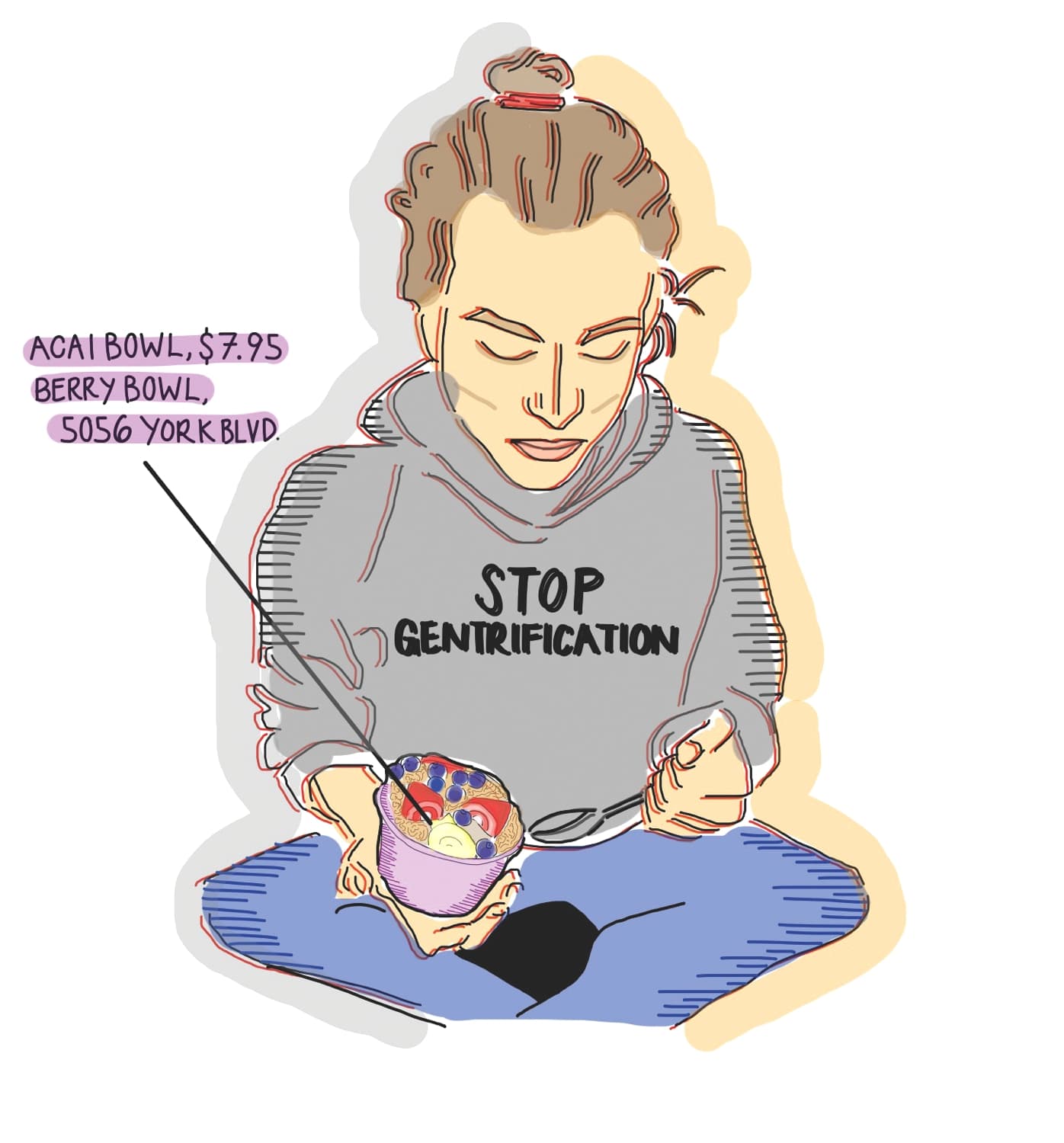

“Middle-class.” “Conformity.” So-called “refining.” You get where this is going. Niche businesses. Açaí bowls. An Icelandic clothing boutique closes and is replaced by a pinball barcade.

This strange, classist cosmetic surgery conjures up a bizarre sentiment at Occidental that I hear all too often: “Gentrification is out of my hands; so what if I eat at Berry Bowl?” However, this logic is flawed: you aren’t fighting something oppressive, you’re complicit in its enterprise. These moments when we turn a blind eye are the height of socioeconomic privilege. But at the same time, it’s true: none of us are capable of single-handedly stopping gentrification. Yes, eating at Berry Bowl isn’t the end of the world, but here’s a different açaí bowl’s worth of thought: we’re all complicit, so we should be conscious of it and use that awareness to inform our decisions instead of throwing caution to the wind because we aren’t directly suffering from the negative effects of gentrification.

Even if gentrification brings material benefits — even to members of the existing community — that doesn’t make it morally or socially responsible. Financial growth should not be the single marker of success, especially if we’re projecting that as a means of deciding who’s doing well in a developing world that we aren’t having to grapple with at that level. It’s inevitable that places evolve and change, yet when these new developments run the risk of drastically altering the constitution of communities that have been present without considering their voices — even if the changes are apparently beneficial to the people who already lived there — we are inhibiting their ability to live in their own communities.

If you think that gentrification can have upsides — namely, economic ones — consider the less tangible things a neighborhood loses when it changes. That is to say, gentrification doesn’t have to visibly displace members of communities to count as a problem. What about cultural shifts that are out of the hands of residents? With all of this new money and all of these new faces, who are the changes truly intended to benefit? Who is being ignored or left behind? This argument of “improvement” in gentrified areas — less crime, a lowered homeless population, better public services — may seem like and in fact be a positive outcome. Yet I wonder why it took an influx of outside people and investors, skyrocketed property values and ultimately new potential market growth in order for a city to be responsible for its citizenry, in order for a place to be more practically attended to by its government.

Gentrification is fueling economic disparity and inevitably people are getting caught in the wake. To overlook them is to continue enterprises of classism and marginalization on spatial, socioeconomic and political levels. This is not up for debate. Even if community members who lived in a place before it was gentrified are not pushed out and share the benefits, which has been proven to not necessarily be the case, consider what the limits of this group are: what about homeless populations being further marginalized by recent developments around Skid Row, or the skyrocketing cost of rent in Santa Monica and Venice? What about the drastic changes that the evolving public transit system is having on spatial relations of different neighborhoods across Los Angeles? I bring this point up briefly, but it’s important to note how much is at stake here.

We have to ask ourselves if gentrification is something that can truly alleviate societal inequity when it’s just another step in the same direction, and when it’s at risk of producing the same social issues faced by communities before its entrance. The same way you don’t fix a wound by inflicting a new one, you don’t preserve a community by making more likely its sacrifice or compromise.

Gentrification isn’t only an economic issue, and thinking about it exclusively like an economic cost-benefit analysis is beyond dangerous. It’s also important to note that these are people we’re talking about — not simply statistics. Boycotting Berry Bowl or á Bloc or The Lodge Room won’t end gentrification, but that misses the point. Suddenly closing your critical moral eye in the name of being passive reveals far more about you than what’s in your wallet.

Karim Sharif is a senior English major. He can be reached at sharif@oxy.edu.

![]()