Living in Arizona, a Republican stronghold turned swing state, I have experienced the whole spectrum of wild conspiracies. This past February, for example, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, one of my customers at the local PostNet gave me a glimpse into his right-wing view of the conflict.

The truth behind the war, as he described it, was about the underground tunnels cutting through Ukraine. These tunnels, the customer explained, gave them the means to smuggle children in and out of the country and had allowed them to establish one of the largest sex trafficking networks in the world. Putin, he informed my boss and me, was an international hero, doing Trump’s work because Trump couldn’t at the moment.

In response to his claim, I did the only thing I could do as an employee at work: smile, nod and try very hard not to express how ridiculous I thought he sounded.

Although conspiracy theories like these may seem outlandish and easy to dismiss — maybe even funny — there’s an underlying danger to these claims that many people find all too easy to ignore. And in the context of the pandemic, conspiracies become even more of a threat.

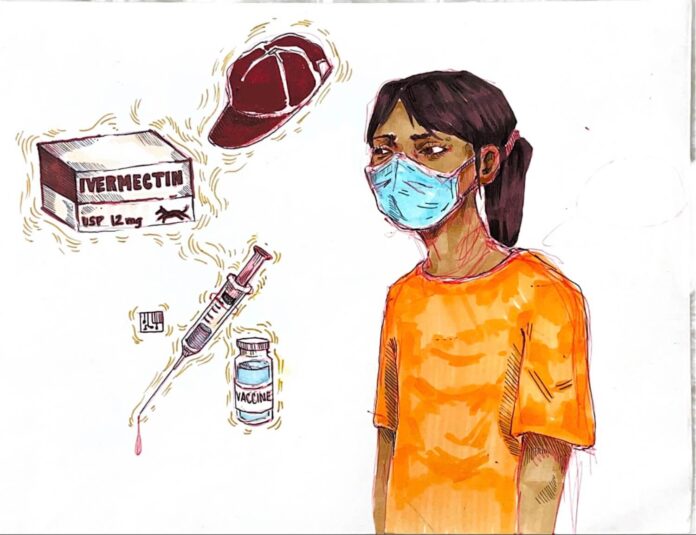

Many theories seemed ridiculous to me — of course horse tranquilizers weren’t going to cure the virus. Yet poison control centers reported that the number of exposure cases of Ivermectin, a medication used to treat parasitic infections, more than doubled from July to August 2021. When I first read that, I couldn’t believe anyone would do such a thing. Then my best friend told me that her grandparents took Ivermectin when they were diagnosed with COVID-19 last year. Despite her grandfather continuing to experience symptoms for weeks, she maintains it was a valid cure.

This same best friend has refused to get vaccinated on the grounds that she doesn’t know the long-term effects of the vaccine. My friend is currently on the pre-medical track, and plans to one day go on to join a host of doctors with more belief in the effectiveness of medicine intended for livestock, than in the science of vaccines.

The modern-day conspiracies don’t stop there. As Jews, my family got a good laugh out of the Marjorie Taylor Greene theory that Jewish space lasers, and not global warming, were the cause of the California wildfires. However, aren’t theories about microchips in vaccines just as unbelievable as the belief in Jewish space lasers? That’s what I thought, yet studies have shown that in 2021, one in five Americans believed that the COVID-19 vaccine likely contained a microchip. That’s 20 percent of our population.

A good amount of conspiracies are fueled on internet spaces, but one cannot ignore the role that our leaders play in encouraging misinformation. In June 2020, Donald Trump hosted a rally at Dream City Church, a megachurch in Phoenix, AZ. Before his visit, the church’s senior pastor claimed that they had an air filtration system which could kill “99.9 percent of COVID within ten minutes.” Over the course of a three-month period during which the Dream City rally took place, research found that Trump’s rallies resulted in at least 30,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases and more than 700 deaths.

My high school shared a parking lot with Dream City Church and rented most of our buildings from them. Most of my high school classes took place in buildings that they owned, and my brother graduated in the same room where Trump gave his speech with the air filtration system that could supposedly stop the virus. My experiences with Trump supporters on campus, where the Trump family continued to host rallies in the following years, led me to realize that seemingly unbelievable right-wing theories about the pandemic were much more prevalent than I initially thought, and government leaders play a big role in that fact.

By making and allowing for claims like the ones that the Dream City Church promoted, government leaders give credibility to ideas that otherwise might not be taken seriously. When random people on the internet encourage us to ignore our doctors and lose trust in science, it feels reasonable to dismiss them. However, when a trusted elected official, supposedly privy to a host of sensitive information, says the same thing, it makes sense that people would believe them. When our leaders take part in campaigns of misinformation or place themselves in a position where it would be reasonable to assume that they might support certain online theories, they give credence to a movement that probably wouldn’t thrive without them. Seemingly ridiculous claims then become dangerous because many people believe them. That harms not only those who believe in those theories, but also the people around them.

It is important that we stop laughing off theories and start fighting the spread of misinformation. Now, as elections approach, we must encourage our peers to fact-check information. We can’t be afraid to call out unsubstantiated claims. Most importantly, though, we must vote for candidates who are open to the evolving study and solutions presented by science and who will help fight the battle against misinformation.

Contact Madalyn Palay at palay@oxy.edu.

![]()