According to Ford, for every one African that was brought to the Caribbean and North America during the Transatlantic Slave Trade, three were sent to Brazil.

“All of those cultures from West Africa [and] Central Africa that made it to the Americas: Brazil became the ultimate mixing space,” Ford said. “Capoeira is a combination of the kicking martial arts, the religions, the work, [and] the various philosophies among the laboring classes of Brazil.”

Ford said the Roda (pronounced Ho-da), a circle formed of people playing instruments and participating in a call and response song, creates space for players to engage in the ritual. Ford said the instruments used in his practice are called Berimbau, which create a Bateria (an orchestra).

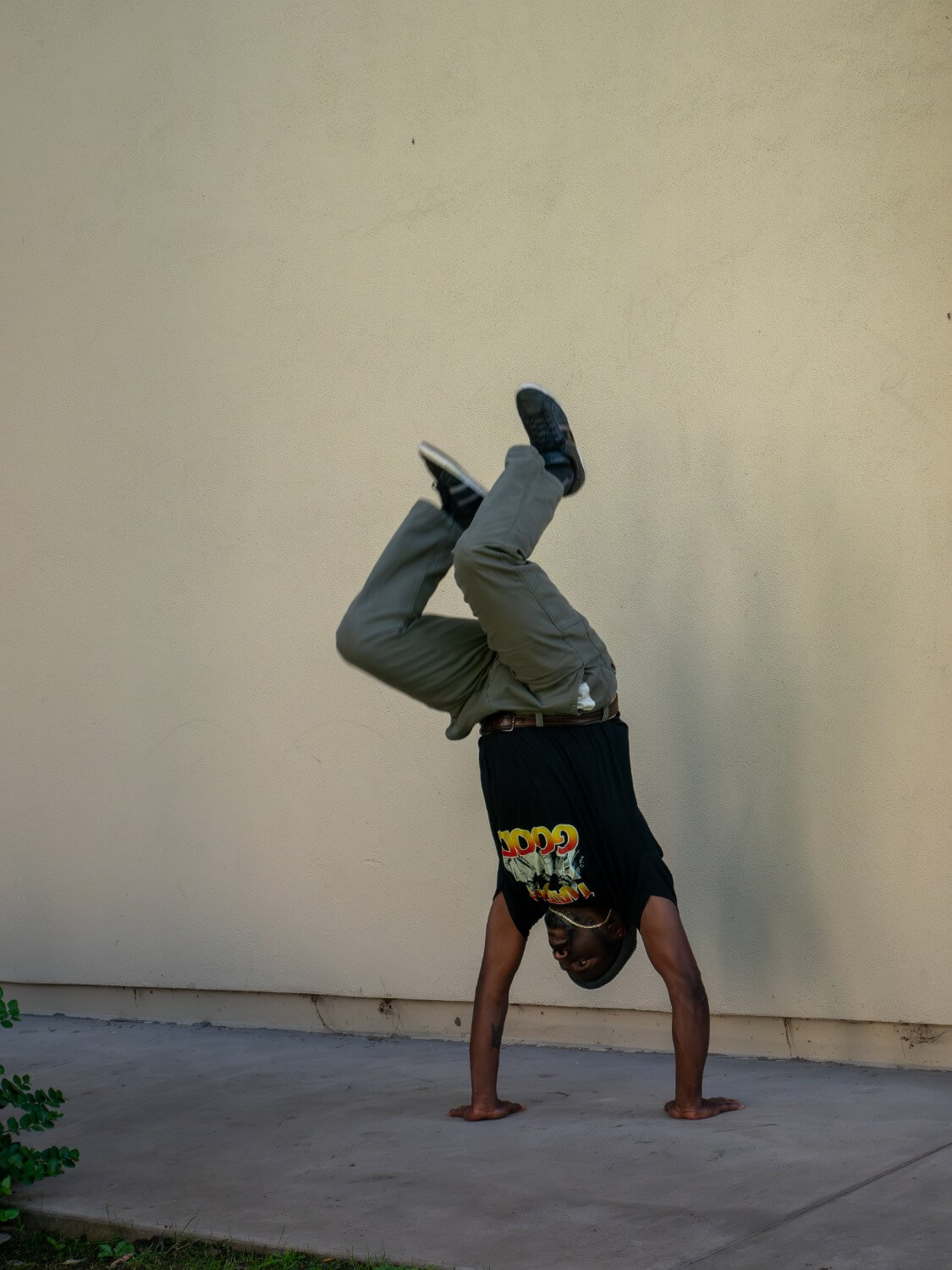

“We don’t say ‘spar,’ we say ‘play,’” Ford said. “Because that’s a more wide-ranging way of talking about the combination of elements.”

According to Ford, the group that shows up to play Capoeira changes week to week, due to the open, informal structure of his sessions.

“It’s just been word of mouth,” Ford said. “Sometimes there’s been a group of students from Oxy who join me, sometimes it’s just local community members, but it’s very enriching for me and the people involved, and that just inspires me to keep going.”

Although the attendance at his meetings fluctuates, Ford’s friend Jaidi Doyle remains a consistent attendee. Doyle said he has been training in Capoeira across the country for decades, and started training with Ford when he came to LA eight years ago.

“I started training in Providence, Rhode Island in the mid 90s, at this place called the Carriage House under this guy who was a student of master Geraldo,” Doyle said. “I used to […] go there to break dance. Then I noticed these guys doing [Capoeira] after the breakdown. I just hung around and I started picking it up.”

Cole Banks* (junior) said they had observed Ford’s Sunday Capoiera from afar with admiration. According to Banks, they taught themselves Capoeira with YouTube videos one summer so they could participate with the group.

“I learned it as well as I could, then came [back to school] and joined them one day,” Banks said. “I’m probably a year in, and I fell in love with it […] I found this community that’s welcoming. Let’s sing and dance and work out together.”

Ford said that in his Sunday practice, he aims to create an atmosphere unlike the fast-paced capitalist reality we live in.

“Occidental students come here being overachievers, and I hope that Capoeira will be a break from that sometimes,” Ford said. “There’s a word that often gets used in Capoeira called ‘vadiando,’ which means hang out, loafing, chilling. […] It’s not loafing like abandon[ing] doing something in a skilled way. […] It’s ‘let’s take a break from labor work.’”

According to Doyle, the interplay between the music, the game and players produces a certain cohesion and spontaneity in each practice.

“Tones and rhythm also dictate the game,” Doyle said. “There’s a story between the three bidding balls like a family. The Gunga is the mother, Médio is the father [and] Viola is a little child. The Gunga holds the rhythm down, she’s playing the same just repetitively […] The Médio does variations, but sticks to the same [beat as Gunga] because they’re a parent to the Viola. [The Viola] can play a little more, do a lot more variation. That [dynamic] hypes up the game when people are playing really well.”

According to Banks, Ford’s teaching style in Capoeira flows throughout his classrooms as well. Banks said they are taking Ford’s Afro-Surrealism class, and that Ford carries himself in the group in the exact way he conducts class.

“[Ford] has been one of the most […] monumental people for me. He welcomes anybody into the space, he looks at you in your ability, and he understands [the] details,” Banks said. “He always has a smile on his face and a joke. He creates a community where, almost like Capoeira, you make fun of somebody and they make fun of you. It’s almost like a fight without actually fighting.”

According to Ford, he feels the philosophy of Capoeira has seeped into his teaching.

“I try to help my students develop a healthy perspective towards grades, and the skills that they’re learning […] a lot of that has to do with what I’ve learned from Capoeira,” Ford said. “When I looked at the people who are further along than me [in Capoeira], they would always say the most important time would be before or after the class, when the masses are talking and they’re gaining knowledge that you can’t really formalize.”

Doyle said Capoeira has emphasized his consciousness of the world around him and its history.

“Capoeira is an art of struggle,” Doyle said. “People use this to escape tyranny and escape oppression. This is a community art, so everybody’s looking after each other.”

According to Ford, Capoeira is a practice that one should take with them beyond Sunday afternoons and into their hereafter.

“The assumption is that it’s with you all of your life,” Ford said. “The way you train, who you train with, and how you train is going to go through phases. The goal is to be a senior citizen, and you can still do it. You may not do all the acrobatic physical moves, but you can still do it.”

*Cole Banks is a reporter for The Occidental

Contact Lucinda Toft at ltoft@oxy.edu

![]()