Seconds after Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl LX halftime performance ended, my phone lit up with messages from family and friends; some expressed pride, while others were moved to tears. My Ecuadorian mother wrote, “Estoy llorando. Qué hermoso ser latina.” (I am crying. How lovely is it to be Latina). Watching the performance unfold alongside those reactions made it clear that this was more than entertainment to me, and to many others across the nation. It felt like one of the most culturally significant halftime shows in recent memory, and one that carried an unexpected sense of hope.

For viewers who had never heard of Bad Bunny (or Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio), despite his roughly 92 million monthly listeners on Spotify and massive global following, the performance may have been unexpected. He spoke almost entirely in Spanish, offering only one line in English, “God bless America.” Bad Bunny did not attempt to translate his words for mainstream comfort, although without understanding every lyric of his discography, you could still sense the passion and pride that defined his performance. No matter what you were doing, he made you pause for a second. Maybe it made you emotional, like my mom and me — or at least made you question why this moment mattered for so many.

Bad Bunny made history just the week prior by being the first Latin artist to win album of the year at the 2026 Grammy Awards. His acceptance speech, in which he said “ICE out,” and “we are humans and we are Americans,” seemed to resonate and complement his performance on the biggest entertainment stage last Sunday.

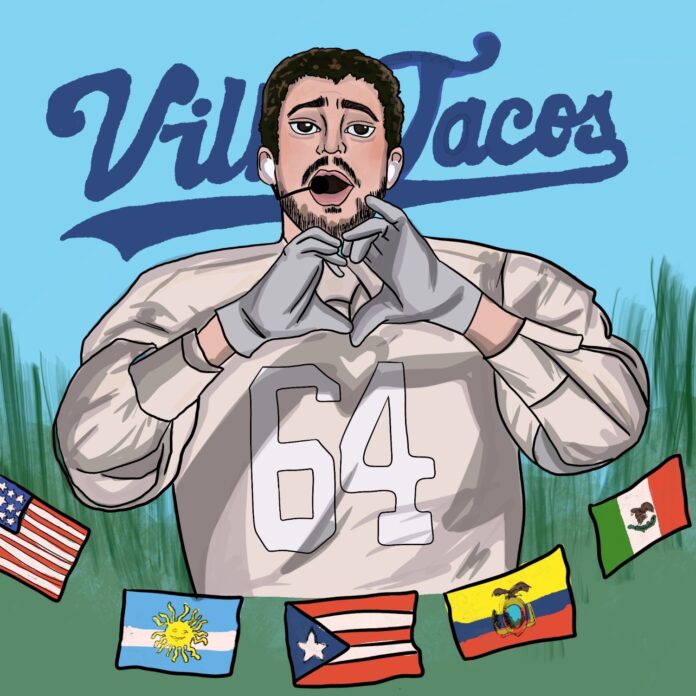

The power of Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl performance came from its meticulous attention to detail, weaving together homages to Puerto Rico and broader Latin culture with a clear message of unity. The stage transformed into a Puerto Rican block party filled with everyday symbols of community life. There were piragua stands selling shaved ice, nail salons, barber shops, domino tables and even our local VILLAS tacos stand, located in Highland Park, all set against a backdrop of sugarcane fields. We see Bad Bunny waking a child asleep in a chair, a familiar scene for many of us Latinos who have experienced celebrations meant to last a couple of hours stretching late into the night.

These scenes paid tribute to essential workers and to the kind of labor that scholar Ava Gotby describes as “emotional reproduction,” the caregiving and service work that often goes unnoticed yet sustains neighborhoods and families. Immigrants and minority communities carry so much of this labor, whose contributions help shape American life. The playful line spoken by Bad Bunny, “Ahora todos quieren ser latinos” (Now everyone wants to be Latino), carried a deeper implication that Latino culture has long influenced American identity, widely acknowledged or not.

At one point, Bad Bunny handed his Grammy to a younger version of himself while saying “Cree siempre en ti” (Always believe in yourself), a gesture that felt like an invitation to future generations to believe in their own possibilities, despite all the efforts made by the current administration to keep them from doing so.

During the song “El Apagón,” power line poles stood prominently on stage, referencing Puerto Rico’s ongoing electricity crisis. Performers dressed as jíbaros climbed the poles as they exploded, showcasing the island’s repeated blackouts and infrastructure failures, further turning the show into a protest against government neglect, colonial history and gentrification.

The core theme of the performance was love and unity, shaping a narrative that felt intentionally hopeful in a deeply divided political climate. Throughout the set, Bad Bunny repeated phrases such as “Están escuchando música de Puerto Rico” (You are listening to the music of Puerto Rico) and “Baila sin miedo, ama sin miedo” (Dance without fear, love without fear), framing music as an act of connection rather than confrontation.

The message reached its peak during the closing moments. After performing his final songs, Bad Bunny named almost all countries from the American continent, ending with “USA,” “Canada” and finally “Puerto Rico.” He lifted a football toward the camera, revealing the words “Together We Are America,” next to the billboard in the background that read: “The only thing stronger than hate is love.”

That emphasis on love as a form of resistance stood in stark contrast to Turning Point USA’s competing event, labeled the “All-American Halftime Show,” which featured controversial performers such as Kid Rock. Even the phrase “All American” clashed with Bad Bunny’s broader message that multicultural identity is part of being American. As someone who navigates acculturation daily, I found that contrast personal. It can feel isolating not knowing which cultural side to align with, yet Bad Bunny’s performance reframed that tension as a source of strength rather than something to overcome. The difference in viewership was striking: roughly 6.1 million viewers tuned in to the alternative broadcast compared with an estimated 125 million watching Bad Bunny’s performance.

President Donald Trump criticized the halftime show, calling it “absolutely terrible” and arguing that it did not reflect American values of “success, creativity or excellence.” His reaction underscored a broader cultural debate about who gets to define patriotism, even though few halftime performances have been as creative in their use of symbolism and in their display of cultural strength as this one.

In a time when shared cultural moments are increasingly rare, Bad Bunny created one that sparked conversation across generations and borders. Whether people loved it or criticized it, they were talking about it. The halftime show did not solve the divisions it exposed, but it gave many a sense of hope that showed love and pride can still bring people together, even if only for 13 minutes. In a moment when political conversations often feel dominated by outrage, this type of exhibition of solidarity may be the only way forward in changing our country’s views on immigrants.

In the end, crying felt like the most honest reaction to a moment that carried so much meaning. Like my mom, I found myself feeling deeply proud to be Latina.

Contact Martina Long at mlong2@oxy.edu.

![]()