Much to the chagrin of the other 29 Major League Baseball teams, the Los Angeles Dodgers are at it again this offseason — just as we’ve predicted in past columns. With all eyes returning to MLB after the Seahawks dominated Super Bowl LX, tensions are already running high in offices throughout the league.

Among myriad smaller roster decisions, the Dodgers landed two more big fish this offseason. The team got started early, as they handed out a three-year $69 million deal to star closer Edwin Díaz in early December. Díaz opted out of his remaining two years with the New York Mets to join Los Angeles where he will earn considerably more per year. The Díaz deal set a record for highest annual value given to a reliever, as the closer will earn an average of $23 million during his time with the club.

What really sent MLB fans and owners alike into a frenzy was the signing of four-time All-Star and World Series champion Kyle Tucker, who signed the dotted line on a record-breaking 4-year $240 million deal. Tucker is now the highest-paid player in MLB, making $60 million on average per year. This beats out the previous record holder Juan Soto, who makes an average salary of $51 million. No matter the outcome of the deal, Tucker is laughing all the way to the bank.

If the Dodgers wanted, they could hand out “bad” contracts until the cows came home. They’ve essentially created their very own infinite money glitch. Despite carrying a payroll of around $400 million (around $60 million more than the second place Mets), money is simply no object.

Perhaps the biggest engine behind the Dodgers money printing machine is their cornering of nearly the entire Japanese baseball market. Shohei Ohtani is to Japan what Taylor Swift is (or was?) to the United States. Coupled with Shohei, the supporting cast of Yoshinobu Yamamoto and Roki Sasaki is enough to turn the heads and gather the spending money of an entire country. Between brand deals and sponsorships, merchandise sales, television deals and tourism the Dodgers have already made back the $700 million given to Ohtani just one year later. This machine is not expected to stop churning any time soon, allowing the Dodgers to operate with biblical greed.

When adding players, the Dodgers rarely weaken their farm or remove players from their MLB roster. The last blockbuster trade they made was for Mookie Betts, who signed a massive extension with the team during the 2020 season. Even then, the outgoing talent of Connor Wong, Alex Verdugo and Jeter Downs hasn’t exactly scorned them. Their aggressive free agent spending nearly every offseason actually keeps the longevity of the franchise afloat.

Of course, no amount of gesturing towards ethical tactics will erase the elephant-sized piggy bank in the room. Following this offseason, the Dodgers have incurred over $1 billion in deferred money. Deferrals have long been a part of MLB’s financial fabric and are historically considered to be beneficial for the sport, but the Dodgers have malformed the practice of deferring contracts to such an extent that they’re the only squad capable of carrying the financial burden. Other teams can emulate this strategy if they like, but when the chickens come home to roost, the Dodgers are the only team that could take a financial hit of that size due to their unprecedented money engine. Ohtani is the goose that laid the golden egg, even if every team had a chance to sign him.

Also responsible for LA’s financial supremacy is the team’s TV deal, an $8 billion behemoth signed in 2014. The deal bears a massively inflated value as part of a compromise between MLB and former Dodgers owner Frank McCourt, who was given a figure on his terms in exchange for his immediate sale of the team afterwards. For those not familiar with economic intricacies, McCourt was essentially paid untold sums of money to go away.

Thanks to McCourt running the Dodgers into bankruptcy in 2011, MLB permitted them to evade revenue sharing over the course of the 25-year long TV deal. This means that LA gets to ignore a yearly $66 million tax that every other large market team is forced to pay, placing that cash directly into their pockets.

If you’ve kept up with the column over the years, you’ll know that MLB spending is currently subject to one of the largest disparities in all of sports. For every high-rolling team like the Dodgers, another 10 teams fail to muster even a third of LA’s spending prowess, and their minuscule payrolls are often reflected in their miserable on-field performance.

The desire to curb this losing tradition may be what’s inspiring numerous owners —namely Dick Monfort of Colorado Rockies fame — to call for the league to implement a salary cap in the next collective bargaining agreement. And while Monfort is right that his club lacks the colossal revenue stream of a big market team, his complaints overshadow a major factor: lots of teams spend money wrong.

Take a glance at MLB’s cellar dwellers and you’re bound to see a multitude of ill-fated contracts. Two of the league’s top spenders — Atlanta and the New York Mets — didn’t even make the playoffs this past season due to a combination of injuries, underperformance and bad luck. Let us not forget the Los Angeles Angels, whose disastrous signing of Anthony Rendon might be the epitome of legalized bank robbing.

Another forgotten but equally important aspect of this recent Dodger dominance is its potential benefit to the sporting world. It’s easy to decry the Dodgers on the basis of the team sullying league parity, but this indomitability has worked wonders for MLB’s ratings. The Dodgers’ 2024 World Series run saw TV ratings surge by 6 million viewers compared to 2023, and 50 million fans worldwide watched Game 7 of this past year’s Fall Classic.

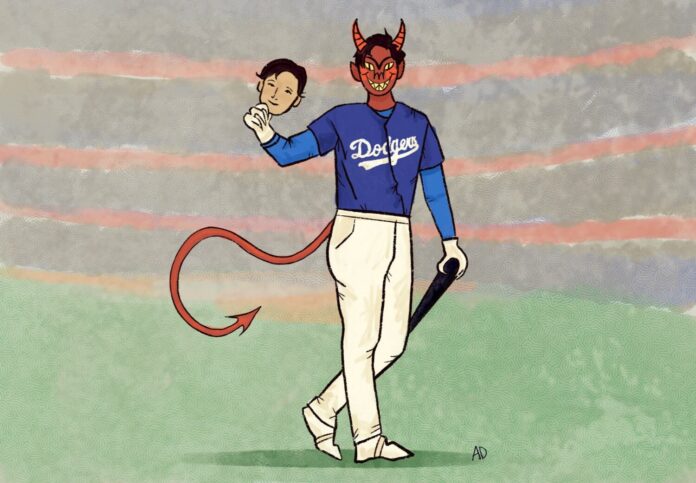

The reason for this ratings explosion is simple — sports fans love having a supervillain to root against. The dynasty-era New England Patriots set records for Super Bowl viewership in 2015, and the NBA finals ratings took a nosedive following the collapse of the Golden State Warriors empire. As it turns out, the same fans who complain of dynastic sports runs tune in with even more frequency.

Even the most ardent Dodgers defender cannot deny that there are obvious flaws with the current state of MLB. Revenue streams are lopsided, parity often feels nonexistent and the league’s top spenders are essentially set in stone on a yearly basis.

Despite these problems, it’s apparent that a salary cap won’t be an instant fix. Baseball’s richest teams will still have an edge in terms of resources and analytics, and no amount of financial guardrails can prevent clueless general managers from ruining their teams.

It might not be the news that most baseball fans want to hear, and it’s certainly not the news we — as lifelong Red Sox fans — want to deliver. Unfortunately for fans of 29 MLB franchises, the stats don’t lie, and they say that the best way to beat the Dodgers is to simply be smarter.

Contact Ben Petteruti at petteruti@oxy.edu and Mac Ribner at ribner@oxy.edu

![]()