Trudging through 2017 is like listening to a mediocre comedian set-up another tasteless joke with a punchline that never comes. Considering that, it’s no wonder that America broke box office records to go see Andy Muschietti’s adaptation of Stephen King’s “It” — a movie about a murderous clown.

I saw “It” as well, and thought it was really fun and well-crafted. That’s not to say it was perfect; the dialogue felt heavy-handed at times, the pacing and tone inconsistent. Still, “It” was visually arresting, highly entertaining and, even though it wasn’t terrifying, it still had plenty of well-earned scares — absolutely worth a watch.

More broadly, though, the film stands as a new milestone in a recent horror movie renaissance, one that has developed over the last few years and produced some of those years’ best films, scary or otherwise. Moreover, this period reveals a cultural shift in film, perhaps triggered by increasingly volatile politics. In uncertain and frightening times, art imitates life.

This revitalization goes beyond the realm of commercially unsuccessful but critically adored independent films. More interesting is that a lot of great scary movies have absolutely murdered at the box office. For example, “Split,” “Don’t Breathe,” “Get Out” and now “It” — the highest-grossing R-rated scary movie ever with over $260 million in box office receipts since its Sept. 8 release — all made over $150 million on relatively small budgets, and all of them came out within the last two years.

Well crafted horror movies in themselves are nothing new. Some of the greatest movies ever made are horror movies — “The Shining,” “Psycho” and “Jaws,” for example — and many, like “Jaws,” have made buckets of money.

Although when I think of the most popular, commercially successful horror movies of the last twenty years, I think “Saw,” “Paranormal Activity” and “The Grudge,” essentially episodes of shock value gore porn spliced together with lazy jump scares — potentially entertaining but thematically hollow.

In the last few years, however, the most lucrative horror films have been those with the most thoughtful narratives and, consequently, the most critical acclaim. “Get Out,” for example, has a 99 percent on Rotten Tomatoes; “It” has an 84 percent.

Personally, I think it has to do with the times. We’re bobbing around in uncertain waters, buoyed on the surface by fear and loathing, trying to see what’s under the water — and it’s not just Trump or Brexit or Syria or climate change. No, some gargantuan, intangible, invisible “thing” is lurking in the depths — something that brings it all together and casts a shadow of dread over what we think we understand.

Horror is best suited to capturing that. Scary stories — good ones — can reveal the most fundamental qualities and abstract anxieties that sit at the core of what it means to be human. They do this more elegantly than any other narrative style by endowing a mysterious and aggressive agent of terror with those anxieties and examining the reactions of the terrorized.

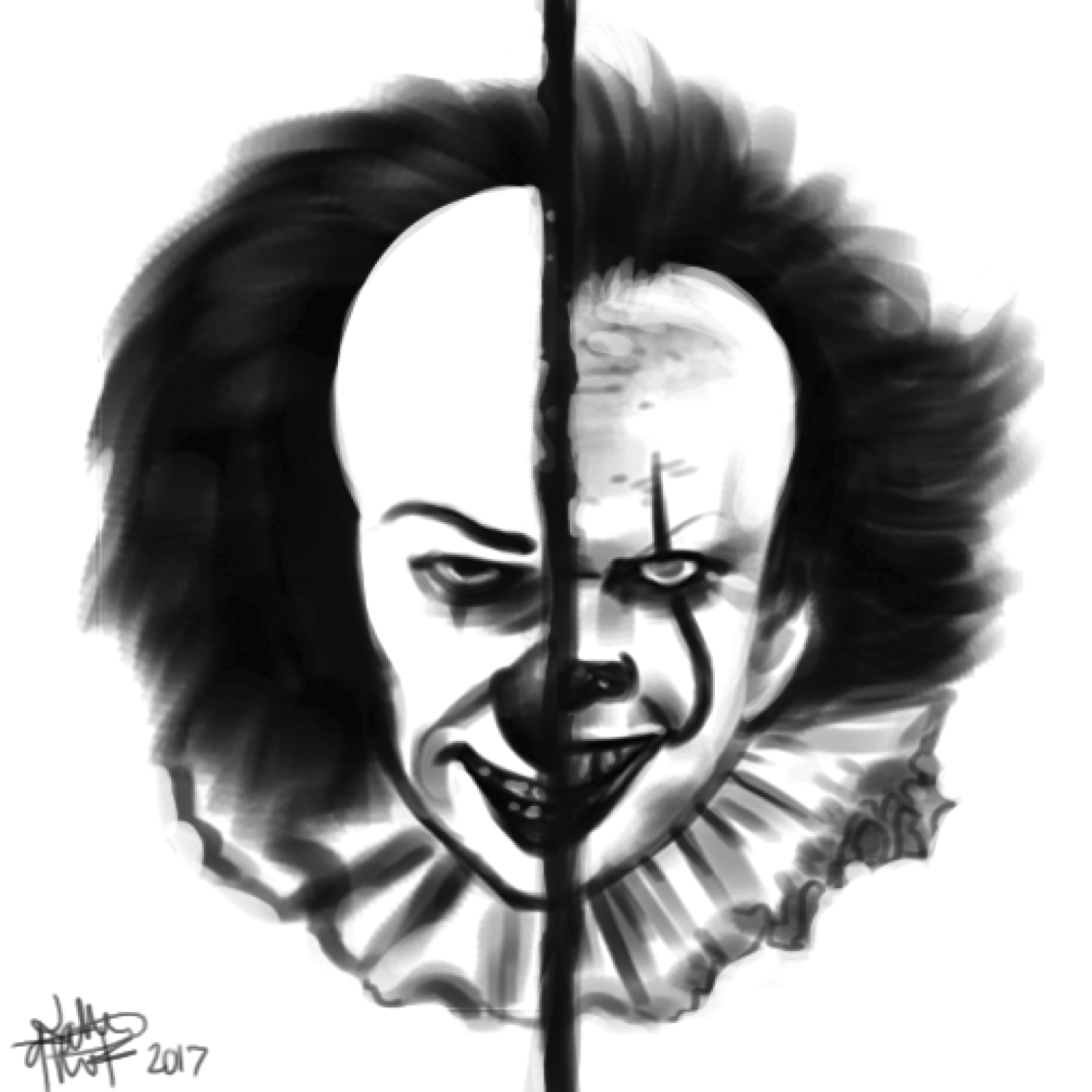

“It” is the perfect example for our modern American anxieties. Although Pennywise the clown is the movie’s monster, he never comes up with any original material. He shapeshifts into the children of Derry’s individual nightmares. He does this to isolate them — to lure them under the town where he keeps them suspended, floating in the sewers forever, literally feeding on their fear.

This is further emphasized in the editing and narrative structure; whenever Pennywise surfaces, it directly parallels the violence from the adults of Derry. These parallels associate Pennywise’s modus operandi of isolation and fearmongering, not only with a transcendent immortal demon clown but also with the toxic culture of the town of Derry — which Muschietti brilliantly realizes as an idyllic American small town, just as King wrote in the original novel.

This forces the audience to consider the pervasiveness of the fear and violence in American culture — and how, by isolating us, it can manipulate and consume us. Only by working together can the kids overcome Pennywise and drive him back into the sewers. Granted, the film can be somewhat heavy-handed on this point, but that doesn’t at all diminish it.

None of these ideas are new. They have sat sunken in the sewers for God knows how long. The difference now is they have floated to the surface. The fear they bleed into the water is unavoidable, especially in an increasingly flooded place.

So, with so much fear out in the world, I would count on a lot more high-caliber horror coming soon to a theater near you.

![]()