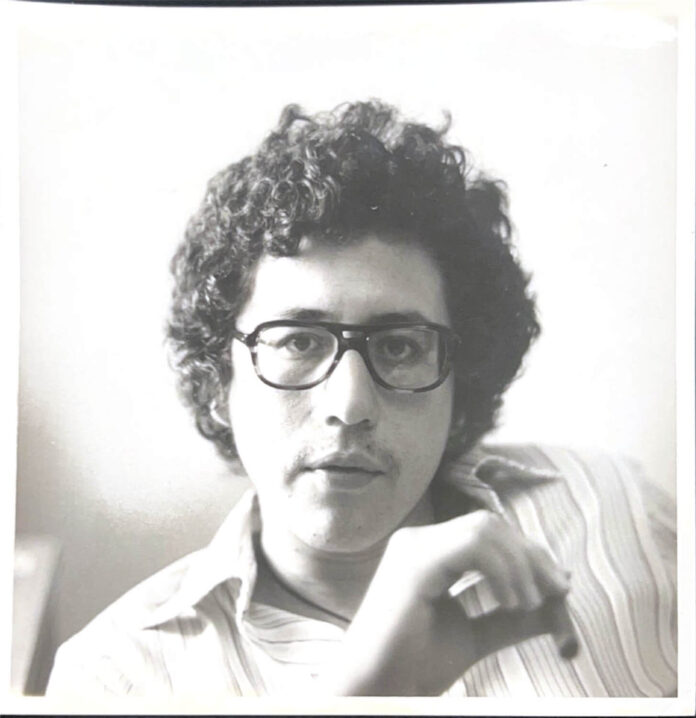

An audience of students, faculty, alumni and community members sat in Choi Auditorium Feb. 20 for “Eyewitness in 16mm: The Early Life of Film and Activism at Oxy.” Co-hosted by Media Arts & Culture (MAC), Oxy Arts and Special Collections & College Archives, the film screening event featured two films and a conversation with award-winning filmmaker Jesús Salvador Treviño ’68.

“Eyewitness in 16mm” began with an introduction by Visiting MAC Instructor Adrienne Adams ’17, who is the guest programmer for the department’s 2024–2025 Cinematheque event series.

“The purpose of tonight’s event is to celebrate the work and life of three people critical to Occidental’s early film history and activism,” Adams said.

The event highlighted Treviño, the late Professor Emerita Mildred “Chick” Strand and Professor Marsha Kinder. According to Adams, Dr. Kinder developed and taught the first film classes at Occidental during the 1960s. Treviño said he was fortunate to be a student in Kinder’s film courses, including one titled, “Global Cinema.” According to Treviño, Kinder taught classes about the pioneers of filmmaking, including Michelangelo Antonioni, Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman.

“[Kinder] would tell us those stories; she was lighting up our consciousness about storytelling,” Treviño said. “She opened my eyes to cinema, [which] lay latent in my life until I became a filmmaker.”

The first film screened was “La Raza Unida” by Treviño. The 27-minute film documents the first national convention of the La Raza Unida Party in September 1972. It was filmed on 16mm film and features frequent close-up shots of the era’s Chicano leaders, such as Raul Ruiz and Jose Angel Gutierrez. According to Treviño, the intimate cinematography reflected his dual role as a documentary journalist and a Chicano activist.

“I wanted close-ups because this was our story,” Treviño said. “I was not in the camp of [objectivity]; I was a fervent believer in La Raza Unida Party.”

Treviño said his filmmaking philosophy is rooted in a humanistic approach to address societal issues, including Latino underrepresentation in domestic politics. According to Treviño, access to evolving technology — from 16mm film to 4K phone cameras — can enable students to document similar social struggles and address ongoing issues.

“Part of it is training yourself to understand the parameters that are being offered — trying to see what you can get away with, so to speak — [while] being careful so that you don’t burn yourself,” Treviño said. “You don’t want to go down flaming with your first project — you want to be around for 10, 20, 30 years.”

Education-in-Action Coordinator Kasio Dalton (senior) said they collaborated with Adams to select the event’s films and that Treviño’s work stands out as an early, powerful example of activist filmmaking. According to Dalton, Treviño’s career path illustrates the dynamic value of a liberal arts education.

“Treviño told an anecdote about getting rejected from five philosophy post-graduate study programs, which ultimately led him to filmmaking,” Dalton said. “In some ways, he’s a case study for how liberal arts can be a really beneficial education — especially for those interested in activism because there’s no one way to be an activist.”

Adams said Treviño’s professional career — with numerous International Film Awards, an American Book Award and widespread television directing credits — stands as a testament to Occidental’s early film and activism history.

The second film screened was “Fake Fruit Factory” by Chick Strand. According to Adams, the MAC department was not formally founded until 2016, but Strand ran Occidental’s film program from 1970–1995. Stand’s 1986 film is a slice-of-life story that follows a group of young Mexican women who create decorative papier-mâché fruit for an American-owned artisan factory.

According to Adams, “Fake Fruit Factory” was selected by the Library of Congress for the National Film Registry in 2012. Assistant MAC Professor Vivian Lin said Strand’s film uniquely prioritizes the women’s informal, sometimes inappropriate, dialogue over individual scrutiny.

“Strand gives them the space to be anonymous by not matching the voice to the face,” Lin said. “When you do that, I think, you create a safety for the people being filmed.”

At the front of Choi Auditorium, a small archival exhibition displayed historic film reels of “Fake Fruit Factory.” According to Special Collections Librarian Helena de Lemos, Occidental’s Special Collections & College Archives houses a Chick Strand collection of films, newspapers and other primary-source material. De Lemos said that archives are important to preserve and protect history such as Strand’s life and legacy.

De Lemos said she appreciated the close-up shots and intrigue of Strand’s film.

“You never see a wide shot or an establishing shot,” de Lemos said. “I’m still thinking about ‘Fake Fruit Factory.’ It made me curious to see her other films.”

After the two film screenings, Adams hosted a conversation with Treviño and a 17-minute Q&A with the audience.

“Eyewitness in 16mm” concluded the 2024–2025 season of Cinematheque — the MAC department’s annual event series. The event’s title is derived from Treviño’s autobiography “Eyewitness: A Filmmaker’s Memoir of the Chicano Movement.”

Contact Julian Villa at villajulian2023@gmail.com

![]()