As a descendant of a genocide survivor, it is truly disappointing to live in a country that explicitly chooses to discount the genocide of 1.5 million Armenians, the trauma of my ancestors and the survival of my Anoog for its own economic gain.

Anoog was my great-grandmother’s aunt. She was 15 years old in 1915 when the Turk her brother-in-law was working for told him to quickly flee with his family because the Turks were coming to their Armenian village. Anoog’s brother-in-law and sister fled to Lebanon. But they were too late to tell everyone about the danger. The Turks killed Anoog’s family and burned her village, but Anoog was able to stay with this Turkish man and work for him in their house. Six years later, she moved to Lebanon. This Turkish man defied his people and saved an Armenian girl who could have easily been killed with her family. I am thankful for him, considering many other Turks would have killed her. I would not be here today if it were not for Anoog.

A hundred and four years later in 2019, I sat down to check my Twitter feed and was startled to see an LA Times headline, “LAPD investigates Turkish flags hung at Armenian schools.”

Holy Martyrs Ferrahian High School in Encino and AGBU Manoogian-Demirdjian High School in Canoga Park were both vandalized with Turkish flags Jan. 29. Overnight, the perpetrators hung the flags on the entrance gates, on the stairways and near the on-site church at Ferrahian. This vandalism, which some victims described as a hate crime, unstitched the barely-stitched wounds from the Armenian genocide of 1915, in which 1.5 million Armenians — including Anoog’s family — were systematically annihilated and massacred by the Turkish government.

From preschool until eighth grade, I’ve attended Armenian schools in LA, including Sahag Mesrob Armenian School and AGBU Vatche and Tamar Manoukian High School. Every day in our Armenian classes, I would be reminded of the atrocities that our ancestors faced. I did research on genocide victims during my sophomore year to learn about the women who were raped, the women who were sold into slavery, the women who were forced to be sex workers and the women whose babies had to be killed along with them.

In these spaces, my teachers encouraged me never to forget my people’s history and resilience. To walk into one of them only to find that Turkish flags had hung there only an hour ago would be absolutely demoralizing. That’s exactly how I felt without physically being there. It infuriates me that Armenian-American students had to experience this trauma firsthand. Armenian school is a place that symbolizes survival, strength and empowerment — but the trespassers treated it as a place of contempt on Jan. 29.

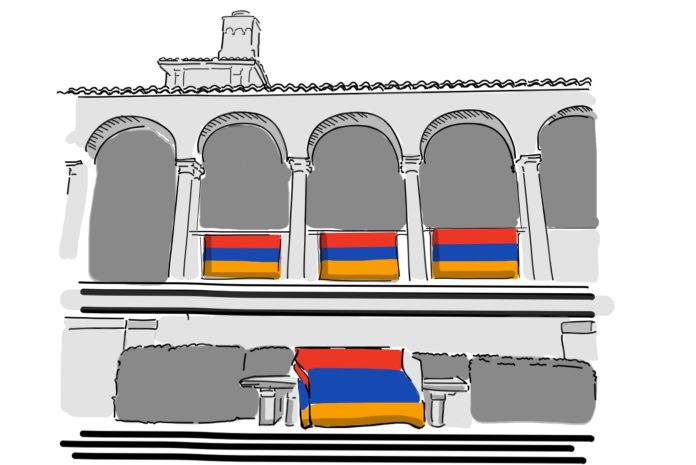

Despite the perpetrators’ hate, my people continue to show their survival as they placed Armenian flags around their Armenian schools in direct response to the event. Occidental College’s Armenian Students Association staged a response to the vandalism Feb. 1. We put up Armenian flags in front of the Marketplace, just as the Turkish flags hung in the Armenian schools, and passed out information sheets about the vandalism. My and my co-president Lara Minassians’ goal as Armenian students was to spread awareness of what happened and is happening in our local community.

The U.S. seems unable to put its pride and capitalistic practices aside when it comes to the tragedies of the people who live in their country. Some, the United States included, argue that there are consequences to labeling the Armenian Genocide as a “genocide.” Turkey has taken measures to make it illegal to use the word “genocide” — and the U.S. is unwilling to lose its ties with Turkey since Turkey is “necessary” for delivering supplies to U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The U.S. is more concerned about its military relationship with Turkey than its own people. The U.S. as a whole is home to about 500,000–2,000,000 Armenians, and our local Glendale is home to more than 50,000 Armenians, earning the name “Little Armenia.” Armenians now have communities in all parts of the world. However, these communities exist due to the forced migration from the killing of 1.5 million Armenians. That is why my mom was raised in Beirut, Lebanon, and why my grandparents were raised in Bucharest, Romania.

Bob Simon, a television correspondent for CBS News, reported on his visit to Deir Zor, a region in modern-day Syria where as many as 450,000 Armenians were killed. During his visit, Simon said to the ambassador of Turkey, “We were in Syria, sir, and we scratched the sand and came up with bones. How can you argue with that?” Even more than a century later, the evidence of the genocide is undeniable.

This is disappointing to my people, especially living in a country that claims to be opportunistic and free. It makes us feel unrecognized and unimportant in our own physical home. My people put their rage into protests and marches in the U.S. for our ancestors — for Anoog.

What can I do as a descendant of Anoog? What do you do as a United States citizen, living in a country that chooses to deny the past? I want to keep Anoog’s legacy, along with my ancestors’, alive, while the United States chooses to deny the history of millions of people. This is not a fight that has ended, but is still occurring, and we will fight for our ancestors like Anoog. Be aware. #StandWithRedBlueOrange

“Heeshom em yev bahanchoom” (“I remember and I demand”) — the Armenian Genocide centennial motto

Serena Pelenghian is a sophomore Critical Theory & Social Justice major. She can be reached at spelenghian@oxy.edu.

![]()