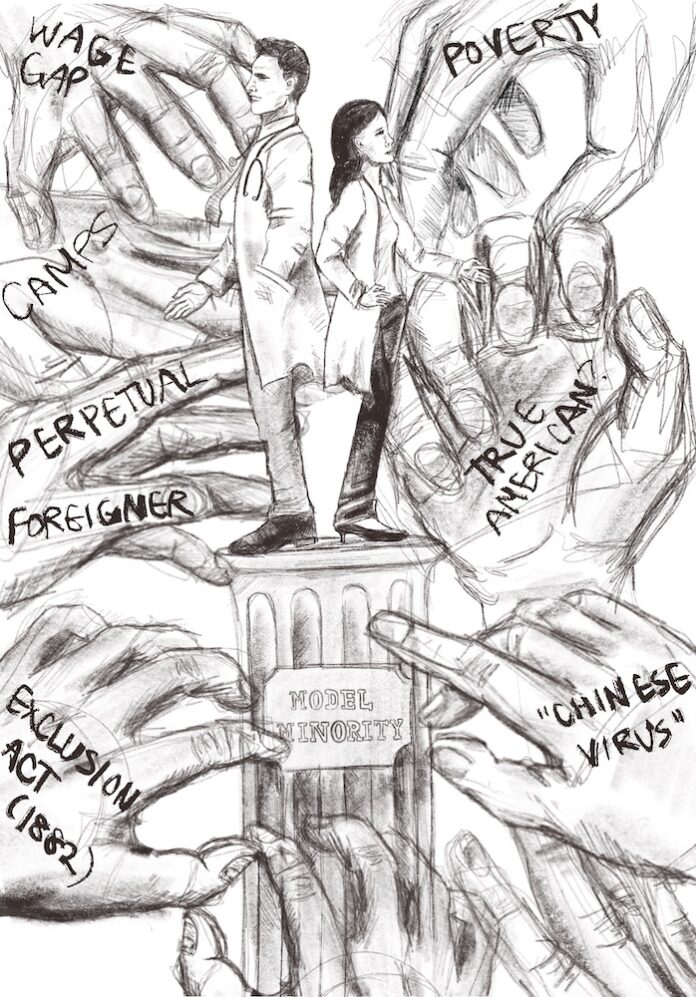

Hate crimes against Asians and Pacific Islanders (API) are on the rise throughout the world. From LA and New York to London and Paris and even across the Pacific in Australia and beyond, attacks directed at API people are a global issue the media is just now taking notice of. The coronavirus may be fueling this recent surge in anti-API violence, but it is far from the cause. Racial violence is inherently tied to global white supremacy and xenophobia, not just as a fear of foreigners but as a violent backlash to the “other.” As a Filipino-Persian first-generation American, I am part of that other.

For POC, this wave of violence is a continuation of that feeling of otherness that comes with living in a world made for the white experience. That feeling comes early. It’s the realization of not looking like your classmates in kindergarten, your parents not looking like your neighbors, people thinking English is your second language, being a minority even though you’re technically the majority and saying your ethnicity before saying you’re American. Xenophobia is not just fear of the foreigner; it’s treating us as foreigners when we’re not.

That internalized otherness becomes more complicated with a mixed-race identity. To own and embrace all parts of your identity is akin to having your cake and eating it too. It’s as if you have to choose a side because for some reason it’s not possible to be both. I can’t help but feel Filipino around other Persians the same way I feel Persian around Filipinos. I can’t help but feel bad when I explain I don’t speak Farsi or Tagalog. I definitely didn’t feel American when people told me they assumed English was my second language, when in reality that was the only language spoken to me growing up.

When getting ready in the morning, sometimes I become fixated on my facial features. My skin is brown like Filipinos’, yet my nose is long and narrow like Persians’. My hair is thin like Asians’, though I easily grow a beard like Middle Easterners. I’m constantly told I look more like my Filipino father, yet he constantly tells me I don’t look Asian. I don’t think I look a lot like my Persian mother, but she thinks I look Middle Eastern enough to get selected for the “random” screening at airports, which the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) picks me for without fail.

Having a mixed identity also comes with the uncomfortable feeling of asking myself where I fit into all the stereotypes passed on by white society. According to ideas enforced by the media, if I look Asian that makes me smart, obedient and docile. If I look Middle Eastern, that’s supposed to be threatening.

If I’m both, I’m neither and if I’m more of one I’m somehow betraying the other. If I’m just American, I’m shunning the rest of my identity. It’s like whatever side you choose you cannot win because to do so you would need agency over identity, a privilege not reserved for POC. On official forms, I am considered a white Asian, a classification I had no choice over. Persians, like all other Middle Easterners, are considered white despite coming from Asia, and don’t get me started on the debate on whether to label Filipinos as Asians or Pacific Islanders. The terms we as POC define ourselves with are colonial. The Philippines, after all, is named after King Philip II of Spain. I still bear that name.

Recently, there has been an influx of Asian voices breaking down the complexities of API identities and the lived experiences of the global Asian diaspora. There have also been amazing pieces of writing about the half-Asian experience. Mixed identity is a nuanced concept that constantly changes as more people share their stories and our lexicon expands to include those voices. That evolution is both immensely liberating and irritatingly restrictive. It’s the feeling of excitement of wanting to be part of the current moment and learn from other Asian voices while sharing my own experiences to make myself and others better allies. It’s also a feeling of uncertainty, isolation and confusion.

The exchange of information and ideas is exponential thanks to the internet and social media. Yet it’s still hard to find where my voice fits into all of this. Sometimes I feel guilty because I don’t feel Asian enough to take up space in conversations on Asian identity. Other times I want nothing more than to use my voice because I am Asian and I am only Asian. We are all products of tens of thousands of years of lived experiences and all the pain and joys that come with existence. I am a product of Asia no different than my ancestors who came before me and I have a right to that identity because I have a right to my existence.

So what can we do to empower all Asian voices in all forms? First, respect that all Asian identities are valid. There is no such thing as being “more or less Asian.” All Asians are part of a global community and we are all equally entitled to be part of that community. Secondly, understand that white supremacy is not just an outside force. By that I mean acknowledge the ways white supremacy permeates our way of thinking and reproduces itself within our families and communities as well as in “progressive” institutions like colleges. Some of the microaggressions I’ve mentioned came from Oxy students. This step requires introspection on everyone’s part no matter how uncomfortable that experience may be. You can start by accessing these resources: from LA-based organizations that support API people to learning about the history of anti-API violence and xenophobia.

Empowering Asian voices also requires us to know all the other ways white supremacy exists in different forms, not just through racism, but through homophobia, the gender binary, patriarchy, global capitalism and neoliberalism. Finally, see us. Don’t just perceive us: I mean really look at us. Look at our communities, our families, our histories, our sorrows, our hardships, our accomplishments, our anger, our happiness, our fear. Behind every headline of violence is a community looking to survive. In every community there is a beautiful array of identities all trying to be seen. You can’t see us if you don’t see them as well.

![]()