This summer, I begrudgingly felt most a part of a community at 8 p.m. on my neighbor’s couch, Trader Joe’s Scandinavian Swimmers at hand and pining over the love arc of “Nicolandria” while watching the hit reality TV show “Love Island USA”.

“Vanderpump Rules” star Ariana Madix hosts the show, dropping 10 ‘hot singles’ in a villa in Fiji, to supposedly “find love.” Islanders participate in challenges, confessionals and recouplings at a fire pit every week or so. “Bombshells,” or new contestants, splash in periodically — aimed at testing the loyalty of solidified couples. The oversaturation of neon tones, bikini dress code and phrases like “It Was Always You” and “Playtime” in bright LED lights on the walls contributed to a quite passé vibe, overall. I always enter a season of “Love Island” thinking I’ll watch it as a gag, but each time it becomes my summer religion.

In recent years, contestants gained mass social media followings and influencer lifestyles due to the show’s increasing popularity. However, this popularity boost led to audience members questioning whether Islanders are on the show for the ‘right reasons.’

In addition to the audience’s intervening presence on the Islanders’ lives post-villa, they had a decisive voice in the show’s happenings through the voting process via the “Love Island” App. The voting plays a central role in the process, since the audience’s most favored couple wins a cash prize of $100,000. The turnout was astonishing, with more than 3 million votes cast.

“I actually really did feel like part of a community,” my neighbor said while looking back at our intensive “Love Island” watch experience this summer. “Love Island” consumed every social media app she opened, and she felt looped in to every comment or joke about an Islander. One night before the airing, we were in line for ice cream, and could hear the people behind us debating the show — and even though we didn’t interact with them, we felt connected.

To my humiliation, there was a point where I couldn’t go to sleep at night until I had watched a TikTok recap of the show’s drama, dissecting the behavior of every Islander and what their choices in that night’s episode revealed about their psyche. “Love Island” generated a mass culture online where suddenly, everyone posting their thoughts on the show considered themselves an expert on socialization and ethical relationship behavior.

On almost every TikTok related to “Love Island” appeared the line “Huda Crashing Out.” This digital obsession with a 25-year-old contestant’s mental state began from the first night, when two Islanders, Jeremiah and Huda, were serious about each other, calling themselves mom and dad of the villa and whispering, “We could win this.” Although the two seemed to be following the unspoken rules of the show, it appeared inauthentic for two people who had just met to seem so sure about one another. The public’s observation was that, similar to other Islanders — Ace, in particular — who merely despised both Jeremiah and Huda, maintained that they were just there to ‘play the game.’

There was nothing more meta than the recoupling of Jeremiah and Iris on the 13th day, leaving the show’s contestants shocked. While viewers were online plotting the downfall of Huda and Jeremiah’s relationship, the Islanders wouldn’t even think to interfere. It then sank in that, as viewers of the show, we actually had power and control over how the plot unfolded — we just had to band together in our voting choices.

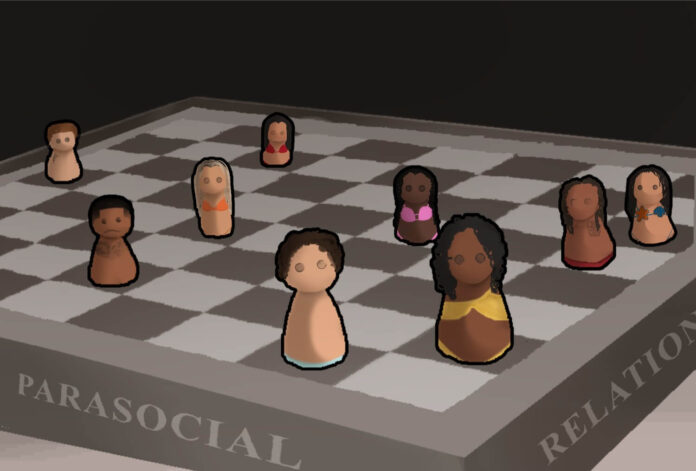

As an audience, we had more say in the Islanders’ future than they did. The social critique of every Islander on social media, combined with their voting power, made the audience feel like we knew what was best for the Islanders without truly understanding them. The “Burst Your Bubble” challenge in Episode 26 demonstrated the audience’s involvement in the Islanders’ perceptions of each other – but also themselves. Islanders had to rank themselves in order in response to a prompt such as “which Islander is the fakest,” or “which Islander would you go on vacation with.” After the self-sorting, Madix, the host, announced how the audience ranked the Islanders, leaving the Islanders confused and shocked.

The external paranoia sank in: how did the audience view the Islanders, where did it come from, and why? The audience loomed, knowing everything about the Islanders’ life choices, yet the Islanders knew nothing about their own viewers.

If “Love Island” is just our guilty pleasure, then why do we remain so morally and emotionally invested? Maybe it’s not about the Islanders at all, maybe it’s about us.

For me, “Love Island” provided a sense of routine and comfort. As a rising junior with no internship, waiting tables six days a week while being stuck at home for the summer, I found excitement in observing the messy lives of hot singles.

Reality TV allows, and even encourages us, to circumvent our intrapersonal problems in favor of critiquing others. And yeah, it’s fun.

Contact Lucy Toft at ltoft@oxy.edu

![]()