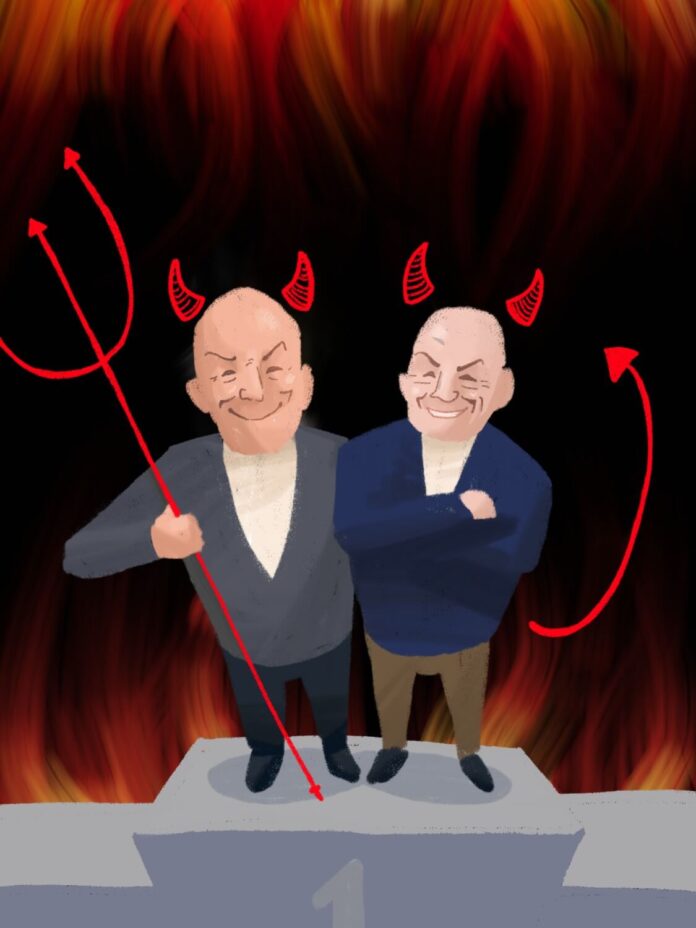

John Fisher and the Athletics

When it comes to the world of Major League Baseball, it’s common to see fan disdain heaped upon team owners as a collective. It’s the unfortunate nature of a league with the largest financial disparity in all of professional sports — while teams like the Dodgers make headlines for obliterating spending records, many of the league’s member clubs prefer to act as though their owners are insolvent. Perhaps no team embodies the miserly spirit like the Athletics, whose putrid on-field performance is only matched by the malevolence of team owner John Fisher.

Fisher is something of an abnormality amongst his billionaire brethren. While the majority of his peers generated their wealth from the ground up or built upon a lucrative foundation, Fisher made his billions through the grueling endeavor of being born to the founders of Gap. After a brief, failed stint working for a real estate company in his youth, Fisher inherited his family’s investment management company and immediately purchased stakes in sports franchises, giving him the rare distinction of having worked exactly one job in his life. It’s no fault of Fisher’s that he was born into luxury, but it’s worth hypothesizing that his immediate exposure to immense wealth led to him approaching the sporting world with the mind of an investor rather than that of a fan.

Pointing out Fisher’s shortcomings as the A’s owner is akin to playing a game of whack-a-mole. Since the beginning of his tenure, the Athletics have been one of the most notoriously parsimonious teams in the sport. Last year, the team’s dismal payroll nearly forced the MLBPA to file a grievance against Fisher for failing to reach spending thresholds. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Fisher ceased payments for minor league players entirely before sheepishly reversing the decision following a torrent of backlash.

Perhaps no story embodies Fisher’s traitorous nature more than the Athletics’ relocation saga in 2023. Despite the prospect of a new stadium that would keep the team in Oakland for years to come, the hopes of A’s fans were dashed after the city balked at the idea of financing a $12 billion dollar ballpark for a team that sported the lowest payroll and attendance in the league. Following the negotiatory breakdown, team president Dave Kaval announced that the team would be bolting for Las Vegas after the 2024 season. All Fisher had to offer was a halfhearted apology letter commemorating the team’s four World Series championships in Oakland and recalling a host of unforgettable moments in A’s history. No event referenced in the letter occurred during his tenure.

As the Athletics’ time in Oakland dwindled, Fisher’s already poor reputation deteriorated into that of a citywide pariah. The A’s, despite continued impotence on the field, became one of the hottest topics in sports as fans organized a “reverse boycott” intended to showcase the undying loyalty of the tortured fanbase. A’s fans, in an attempt to dispel narratives that they had abandoned the team, endeavored to pack the stands for an otherwise unimportant contest. The event was a smashing success, with over 27,000 A’s diehards (more than triple the average attendance that season) swarming the Oakland Coliseum in one final act of defiance against apathetic team management. As the chant of “Sell the team!” filled the air, Fisher was nowhere to be found, and the question of which party had given up on its counterpart was resoundingly answered. The day served as a stark reminder to the baseball world — an abandoned fanbase, all but left for dead, still pulsated with life.

Jerry Jones and the Dallas Cowboys

In the realm of the NFL, perhaps no other owner receives as much flak as Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones. Jones started off with an immediate advantage, as he started working for his father’s insurance company after he graduated college. He then took that capital and started his own oil and gas business, Comstock Resources. In 1989, Jones flipped those profits to purchase the Dallas Cowboys for about $150 million. Jones immediately fired massively popular two-time Super Bowl winning coach Tom Landry and replaced him with Jimmy Johnson. Largely thanks to the Herschel Walker trade in 1989 (one of the largest and most one-sided trades in the history of sports), Jones and Dallas gained the draft and player capital to go on a massive run. The team saw success early, winning the Super Bowl in 1992, 1993 and 1995. As the Cowboys’ ’90s dynasty cemented itself, it became clear that Jones intended to run the team like a business despite its status as a national icon. For the better part of a decade, the Cowboys performed like “America’s Team.”

Jones always focused on the business side of his team. After acquiring the team in ’89, he immediately looked to secure television deals, market the team’s success and turn the stadium itself into a museum that would attract visitors. The Cowboys played at Texas Stadium in Irving from 1971 until 2009. The stadium famously featured a partially open roof “so God could watch His favorite team play,” according to Cowboys linebacker D.D. Lewis. Since moving to AT&T Stadium in 2009, tours and merchandise sales have been a top priority for Jones. A testament to Jones’ massive ego, AT&T is a gargantuan complex that caters to Cowboys fans’ deepest materialistic desires. Imagine a mall within a museum. Then plant a giant football field in the middle of it all. The stadium itself is connected to the Cowboys’ sprawling practice facility, “The Star,” which guests can also tour when they visit.

Numerous players have complained over the years about feeling like a spectacle during practice, but that certainly won’t stop Jones. Stadium tours generate $10 million yearly, not to mention the bonus income they funnel to the Cowboys’ massive merch system. Jones and his kin have constructed a merchandise empire mostly separate from the NFL’s reach. Merchandise generates an estimated $200 million annually for the Jones family. Combining a football team, a museum, a mall, a stadium and an entire practice facility has created a $13 billion business conglomerate. In recent years, it’s become abundantly clear that the focus is the business, not the football team.

Unlike the other 31 teams in the NFL, Jones not only functions as the team’s owner, but also as the team’s president and general manager. It’s an unprecedented consolidation of power. Jones’ oldest son Steven serves as the team’s co-owner, executive vice president, CEO and director of player personnel. His youngest son, Jerry Jr., is the chief sales and marketing officer as well as executive vice president. Jones’ only daughter, Charlotte, is the team’s chief brand officer and third executive vice president. Every aspect of the Cowboys is managed by the Jones family. Outside talent in their executive positions is almost unheard of.

Perhaps it’s no surprise then that the Cowboys haven’t appeared in a conference championship game since 1995. In the recent Netflix documentary “America’s Team: The Gambler and his Cowboys,” Jones compared running the Cowboys to a “soap opera.” Without the drama and discontent, there wouldn’t be a business. The tours would stop coming, and jerseys would cease to fly off the shelves. The team constantly has America’s attention, but for all the wrong reasons. Since the ’90s, the team has suffered countless wild card and divisional round choke jobs. Despite winning a wild card game in 2023 and retiring the legendary Tom Brady, they were easily bounced in the divisional round by the San Francisco 49ers, who have shut them down multiple times in the playoffs the last few years. In 2024, the team suffered an embarrassing defeat at AT&T Stadium against the Green Bay Packers, turning the very fact that the Cowboys made the playoffs into a mockery.

Despite this constant failure, Jones still can’t get out of his own way. After a nearly two-year-long contract dispute, the Cowboys traded star linebacker Micah Parsons to the Green Bay Packers after getting blown out by them at home just a few months ago. Parsons was making a name for himself as one of the best defensive players in the league, but despite owning a $13 billion franchise, Jones wouldn’t pony up to offer Parsons a respectable extension. How can you direct a soap opera when you let the lead actor walk?

With the best defensive player on the team gone, the Cowboys are slumping sideways. If the money doesn’t come from winning, then why pay the players? Jones and his family have made their bed. Mired in mediocrity, they have sealed themselves in their fate as the perennial laughing stock of the National Football League.

While Fisher’s legacy as the Athletics’ owner has been tarnished since it began, Jones’ story is that of a man whose ego and obstinacy spoiled one of the greatest dynasties in all of sports. Ultimately, two men who have only known wealth sullied both of their once-proud franchises in the pursuit of the almighty dollar. Perhaps a tale like this is unsurprising in a world inundated by the ills of its richest inhabitants. To a sports owner, a team may merely be a vehicle for driving a profit. But that mentality is the ultimate disservice to the fans pouring their livelihoods into the team, making it more than just a business.

Contact Mac Ribner at ribner@oxy.edu and Ben Petteruti at petteruti@oxy.edu

![]()

A truly well-researched and well-written article that taught me a great deal, while I was enjoying the read. Keep the articles coming!